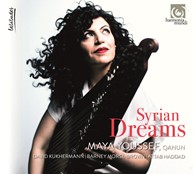

Newcomer Award (sponsored by ISM)

Maya Youssef

Syrian Dreams (Harmonia Mundi)

Maya Youssef talks to Simon Broughton about memories of her homeland

In 2012, I saw news footage about a little girl dying in her bedroom in Damascus and I closed the door and this music came out of me. I was so emotional and it burst out in such an intense way…” Maya Youssef tails off because the sentence doesn’t really need to be finished. We’ve all seen horrific footage from Syria, but it is impossible to imagine the effect the countless human tragedies – like this little girl – and the destruction of beautiful cities like Damascus and Aleppo must have on those who are exiled and can only look helplessly at what is happening at home.

The piece Maya Youssef wrote, ‘Syrian Dreams’, begins like a sorrowful lament, but evolves into something louder and more insistent, before ending with a curious rising note, like a musical question mark. “If I don’t write I’ll explode. I was so angry and heartbroken,” she adds. “‘Syrian Dreams’ is a prayer for peace, I was just praying for peace when I was writing it.”

Youssef plays the qanun, the Arabic zither that is at the heart of Arabic music. The word, originating from Ancient Greek, literally means ‘rule’ or ‘law’ and it’s where the legal term ‘canon’ comes from. The instrument, with 78 strings, ranges over three-and-a-half octaves and is played on the lap or on a table. It’s plucked with plectrums on the index fingers, creating an incredibly intricate sound, although on her album you hear percussive sounds and ferocious glissandi as well.

At London’s Barbican Centre in September 2017, she played with the Iranian duo Adib and Mehdi Rostami in what they call the Awj Trio. Although the Arabic and Persian musical traditions are different, there is much in common in musical modes and improvisation. Flanked on one side by Mehdi Rostami on setar (lute) and on the other by Adib Rostami on tombak (drum), the delicate sounds of the two plucked instruments blended seamlessly, revealing the extent of their musical training.

Youssef started learning the violin aged nine at the Solhi al-Wadi Institute of Music in Damascus. But after just a couple of lessons, she was in a taxi with her mother when the sound of a qanun came on the radio. “It blew my mind. From the moment I heard it, I knew that was what I wanted to play,” she says. “It is so deep, like a well. You can never get to the end of it.”

However, the taxi driver said that girls simply don’t play qanun. But the music institute switched her to the qanun class and she went on to graduate (in 2007) from the High Institute of Music and Dramatic Arts. There are other women qanun players across the Arab world, but they are a tiny minority.

“My father is a writer and journalist and my mother is a translator,” Youssef says. “They were both music lovers and encouraged me. My mother’s tastes were more traditional – the great Arabic singers like Oum Kalthoum – and my father’s tastes were more eclectic, so I grew up listening to Jan Garbarek and Zakir Hussain, Tibetan monks, Miles Davis, João Gilberto and experimental string quartets.”

When she was at the music institute in the early 2000s the training was basically Western-oriented with solfeggio, harmony, composition and history of Western and Arabic music. “My qanun teacher was Azerbaijani (Elmira Akhundova) and I had to go to a private teacher for my real Arabic music training, although they’ve caught up since,” she chuckles. “I studied with Salim Sarwa, who was Syria’s greatest qanun player. And I had masterclasses from Turkish master Göksel Baktagir.”

The Turks are renowned for their kanun (Turkish spelling) technique. The Arabs simplified their tuning at the famous Cairo Congress in 1932 and divided each tone into four quarter tones. The Turks divide each tone into nine ‘commas,’ creating much finer nuances. Each note on Youssef’s qanun has four levers to adjust the tuning, on a Turkish kanun each note has nine. “There is a recent craze for Turkish-style music and some players want to ditch their Arabic qanuns. In the past, you’d go to a qanun player in Aleppo and he’d be playing in Aleppo style, but now you might hear an Aleppo player playing on a Turkish kanun in a completely Turkish style, which seems a shame to me. The Aleppo style is about savouring the space around the notes. It’s not as technically complex, but it lets the notes work in a deeper way. I love both and use both.”

Her qanun is a work of art, made by an Aleppo maker called Nabil Qassis. It is fashioned out of white maple – like Stradivarius violins. The strings are crystal so they don’t break and the levers are chrome so they never rust. It’s finished off by her name in Arabic calligraphy. “Qassis stayed in Aleppo till about a year ago, although he was targeted by a sniper on his way to his workshop every day. He did get shot in the ankle, but survived. He left for Denmark about a year ago and is too traumatised to work any more. He’s the best qanun maker I’ve ever seen.” So qanuns are also casualties of the war.

In 2003 Youssef started a band called the Syrian Female Oriental Group. The seven-piece group included a singer plus oud, qanun, nay, violin, cello and percussion. They toured internationally in Germany, Holland, Greece, China and more. After she graduated in 2007, Youssef went to Dubai and, without a band, was playing qanun for about ten hours a day. “Every player goes through an imitation phase, an innovation phase and then starts to find themselves – that’s what I was doing in Dubai. I got a lot of media attention as a soloist.”

Then she was offered a faculty place to teach qanun and Arabic music at the Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat, Oman. “It was a great opportunity, but as a performer when you don’t perform you feel like you’re slowing down and I’m genetically built to be on stage.”

Then came the revolutions of the Arab Spring in Tunisia in December 2010 and Egypt in January 2011. Syria was slower to get started, but the consequences were much worse. The civil war is now in its seventh year with close to 500,000 civilian casualties (according to the UN) and over five million refugees outside the country. Maya Youssef applied in 2011 for a UK visa under the Arts Council’s Exceptional Talent Scheme and moved to London in January 2012. She now has a seven-year-old son and for safety reasons is not keen to return to Damascus, although her parents are still there. So currently, the only way of revisiting Syria is through her music.

Her album Syrian Dreams is produced by Joe Boyd and recorded by Jerry Boys – famed for his Buena Vista Social Club recordings. In a trio, she plays with Barney Morse-Brown on cello and Sebastian Flaig on percussion. Aside from the title-track, there are two other pieces that relate to the war. ‘Breakthrough’ is about the resilience of refugees who don’t give up. “It’s a tribute to the unbreakable human spirit.” And ‘Bombs Turn into Roses’ comes from a dream she had. “In the dream I am looking up to the sky with these bombs falling slowly on me, but before they hit they turned into white rose petals. I wish all bombs would turn to rose petals, but that is only in my dreams.”

Perhaps the most ambitious track is ‘The Seven Gates of Damascus’, which briefly evokes each of the seven gates of the Old City of Damascus – some dating back to Roman times. Historian Ibn Asakir said the gates were built in alignment with the planets to bring peace and prosperity to the city. Each of the gates has the name of a planet carved on it – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, plus the moon and sun. And Youssef refers to Al-Kindi’s ninth-century treatise on Arabic music in which he outlines cosmological connections to music. So Youssef has given each gate its own maqam and weaves an 11-minute suite from the tiny Bab Al-Saghir (The Small Gate) to the lively Bab Sharqi (Eastern gate). “Bab Al-Saghir is a little place in a conservative part of town where the roads are very narrow,” she says. It’s connected to the planet Jupiter – certainly not small – and depicts it with a low melody on solo oud, played by Attab Haddad in maqam Ushaq. “Bab Sharqi is connected to the sun and maqam Rast, which is very fitting. You can call it touristy because all the amazing restaurants are there and also my favourite sweet shops. It’s an old gate but very young in spirit.”

Anyone who’s had a glimpse of the rich culture of Syria despairs at the destruction and everyone despairs at the loss of life – still with no sign of an end. “All most people know of Syria is war and people dying, but hopefully what I’m doing is showing people a glimpse of an amazing rich tradition.”

The Newcomer Award is sponsored by ISM