Thursday, October 31, 2019

At home with Ali Farka Touré

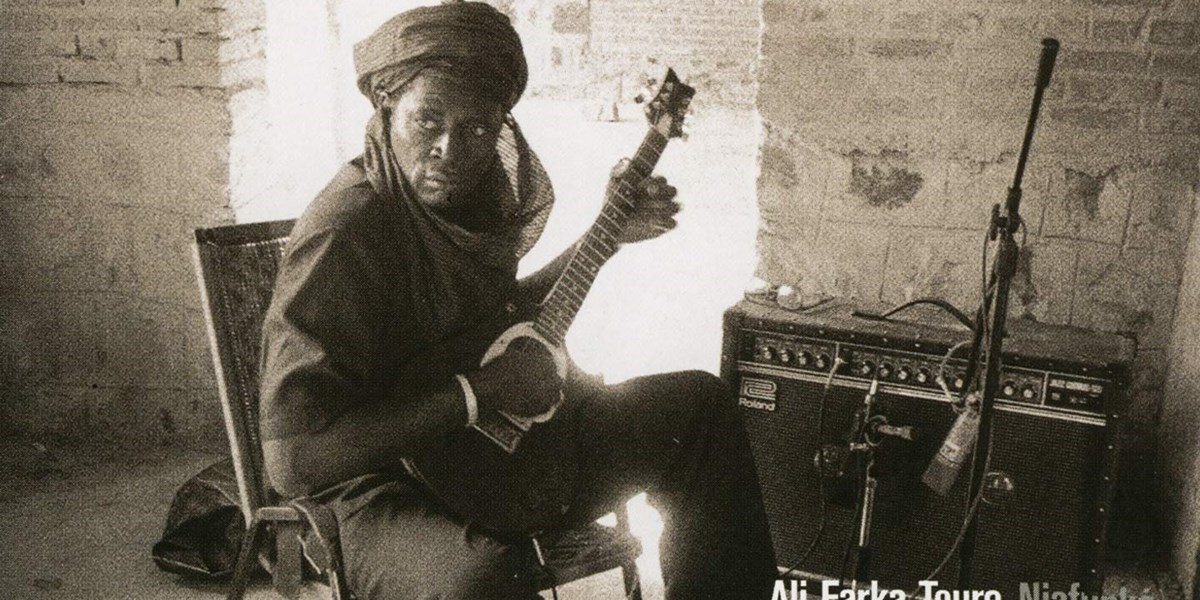

To record Ali Farka Touré’s album 'Niafunké', World Circuit took a mobile studio all the way to Mali. Nigel Williamson went to meet Touré for Songlines in the summer of 1999 and found out why his commitments at home meant that the mountain had to go to Mohammed

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting the Songlines website, your guide to an extraordinary world of music and culture. Sign up for a free account now to enjoy:

- Free access to 2 subscriber-only articles and album reviews every month

- Unlimited access to our news and awards pages

- Our regular email newsletters