Tuesday, July 17, 2018

The Rough Guide to World Music: Australia

By Seth Jordan

The story of Aboriginal music is centuries old and continues to develop in fascinating ways

Yothu Yindi at the Garma Festival

Note that this Rough Guide to World Music article has not been updated since it was originally published. To keep up-to-date with the best new music from around the world, subscribe to Songlines magazine.

With a remarkable history that stretches back at least 50,000 years, the indigenous people of Australia are part of one of the world’s oldest cultures. Preserving their ancient heritage through a complex oral tradition of mythological “Dreamtime” stories, music has always played a central role in maintaining cultural identity, ancestral lineage and an enduring connection to the land. From the traditional sounds of voice, bilma (clapsticks) and yidaki (didgeridoo) through to contemporary singer-songwriters, rock bands and the latest Aboriginal hip-hop, Australia’s indigenous music continues to evolve in fascinating ways. Seth Jordan tells the story.

In the Dreamtime

Aboriginal creation myths tell of legendary totemic beings who wandered over the continent in the Dreamtime, singing out the name of everything that crossed their path – birds, animals, plants, rocks, waterholes – and so singing the world into existence. The songlines are paths which can be traced across the continent, linking sacred spirits that have returned to the land – a kangaroo that has turned into an outcrop of rocks, perhaps, or a giant lizard into a mountain range. Tribal groups regard these totemic beings as ancestors and thus may have, for example, a local Rainbow-Serpent Dreaming or a Honey-Ant Dreaming which incorporate the story of their creation and can be depicted in art or retold in song.

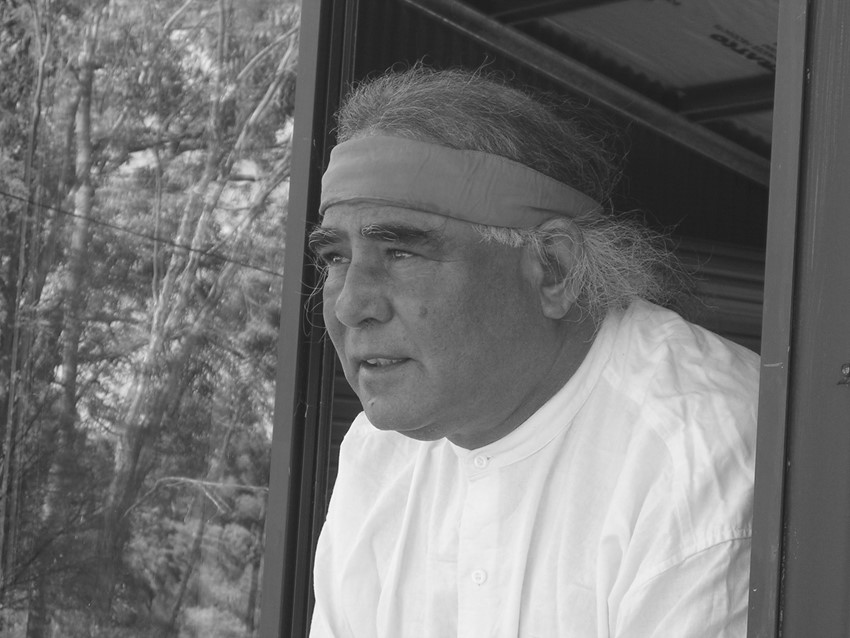

Mandawuy Yunupingu of Yothu Yindi (photo Emmo Reiss)

The songlines define the intangible relationship between Aboriginal music, beliefs and the land. As Mandawuy Yunupingu from the popular band Yothu Yindi explains: “The role of song in Aboriginal or Yolgnu Creation is what creation is all about. The song is creation. The art is creation. The specialness in that is that we have a heart-and-mind connection to Mother Earth. Songlines are entrenched within the land itself, the journey of the songlines is from the east to the west, the journey is about following the sun.”

According to Bruce Chatwin’s book Songlines, the ancestors are thought to have scattered a trail of words and musical notes along the lines of their Dreaming-tracks. An ancestral song is thus both map and direction-finder, an essential requirement in the unforgiving environment of Australia’s outback: “Regardless of the words, it seems the melodic contour of the song describes the nature of the land over which the song passes. One phrase might say, “Salt-pan”, another “Creek-bed”, “Spinifex”, “Sandhill”, “Mulga-scrub”, “Rock-face” and so forth. An expert songman, by listening to their order of succession, would count how many times his hero crossed a river, or scaled a ridge – and be able to calculate where and how far along a songline he was.”

Chatwin also maintained that while a songline might pass through the country of various language-groups, the melody may intrinsically remain the same. In this way, if two neighbouring groups are allied and agree to trade the geographic “lyrics” of their songs, members of each group can safely travel through the country of the other. Having learned a new “verse”, the extended song simply covers more territory. Some songlines reportedly stretch across the entire continent.

As the name songlines suggests, music and song are central to Aboriginal identity. Through singing, dancing, painting and ceremony, people become co-participants in the ongoing creation and re-animation of life. Songs can contain the history and mythology of a clan, the practical instructions for the care of land or advice about dangerous foods and animals.

Traditional Aboriginal music is strongly rhythmical, with a dependence on natural sounds – handclaps, body slaps, the stamping of bare feet on the ground, or the clapping together of bilma and boomerangs. The best-known instrument is, of course, the didgeridoo, which gives either a pulse or sustained accompaniment to a dance, sacred ceremony or corroboree – a meeting of neighbouring tribes. The instrument’s deep, resonant sound is instantly recognizable and has become the most popular and distinctive feature of contemporary Aboriginal bands.

A Bit of History

The indigenous people of Australia are thought to have arrived between 40,000 and 100,000 years ago. Clans may have migrated through Southeast Asia, though this has not been proven. There is genetic evidence which indicates a common link with East Coast Africans and southern Indian Dravidian peoples, which may suggest an original arc of migration from Africa. There are also strong genetic and linguistic similarities between some Aborigines and the peoples of modern-day New Guinea, although this may be as a result of more recent trade and intermarriage.

While some of Australia’s northern indigenous peoples traded successfully for centuries with visiting Macassan seafarers from Sulawesi (formerly Celebes), European exploration of the continent only began in the early 1600s, with Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish and French sea captains. It wasn’t until 1770 that English explorer James Cook claimed the continent for Britain, which he justified by the legal concept of terra nullius (“no man’s land” or “empty land”) – a distinctly European idea defined as “an absence of civilization”, since no other colonial power had previously laid claim to it. This was despite the fact that the continent already had somewhere between 300,000 and a million inhabitants, speaking at least six hundred distinct languages.

From 1788, the indigenous people were driven off their ancestral lands and resettled, or simply hunted and killed like animals. Such brutal practices persisted until well into the twentieth century, and discrimination has continued, with the recognition of Aboriginal rights a relatively recent development. European settlement also meant the suppression of traditional languages, ceremonies and culture, the denial of identity, the importation of European diseases and the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

In the late nineteenth century, Christian missionaries established mission stations in remote areas, rejecting the “heathen” music and culture of the Aboriginals and teaching them European hymns. The strong influence of gospel singing can still be heard in Aboriginal choirs and the work of some indigenous singer-songwriters.

There are currently over 450,000 people in Australia who identify themselves as indigenous (2.4 percent of the population) and some two hundred surviving languages. As well as the mainland Aborigines, the Torres Strait Islanders – of Melanesian descent – inhabit the islands between the coast of Queensland and Papua New Guinea. The vast majority of Aboriginals are scattered across the continent in country towns and settlements, with concentrations in the urban centres. While in some areas Aborigines are well integrated into Australian society, elsewhere there is continued deprivation, unemployment, high rates of incarceration and domestic violence, and ongoing problems with education, health and alcoholism.

Since the late 1970s, Aboriginal music has become an important vehicle for expressing the struggles and concerns of Aboriginal people, and in educating listeners from the outside world. Modern Aboriginal music is often closely aligned with the political struggle over land rights. Music has consolidated its place as a cultural glue, holding the people together and educating the public.

On the 1995 compilation album Our Home Our Land, Yothu Yindi’s song “Mabo” celebrated the historic 1992 legal case in which the Australian High Court overturned the terra nullius doctrine:

Terra nullius, terra nullius,

Terra nullius is dead and gone

We were right, that we were here

They were wrong, that we weren’t there . . .

Preserving the Past

The first known wax-cylinder recordings of indigenous Australians were made in 1898, on islands in the Torres Strait. Recordings were also made in Tasmania in 1899 and 1903, and in South Australia and the Northern Territory in 1901 and 1912. An important modern cultural development for Aboriginals was the establishment in 1964 of the Institute of Aboriginal Studies in Canberra, now known as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). This has sponsored research into all aspects of traditional Aboriginal life, including a priceless archive of over 7000 hours of indigenous music, collected from 1898 to the present.

For most white Australians, traditional Aboriginal music has been a primary, if marginal experience of Black Australia. Its otherworldliness has maintained the image of Aboriginal issues being on the periphery of “Australian” life, and it has received very little mainstream attention outside anthropological or ethnomusicological circles.

One in-depth study of traditional Aboriginal music is the book Songs, Dreamings and Ghosts by Professor Allan Marett. Much more than a dry academic exercise, it gives a detailed analysis of the wangga (song and dance) of the Daly River region of Northwestern Australia. Marett’s work with senior songmen and women sets a benchmark for future research into Aboriginal music.

Country Roads

Since the 1950s one of the strongest influences on contemporary Aboriginal music has been country music. Considered unlikely musical bedfellows by some, the two genres actually have a lot in common. As most Aboriginal people continue to live outside the major urban centres, the appeal of rural subject-matter is obvious, and for many years country artists were the only musicians who regularly toured and performed in those regions. As documented in Clinton Walker’s definitive book (and accompanying CD/DVD) Buried Country: The Story of Aboriginal Country Music, “Not only did Aborigines share a large part of country’s roots (gospel music, minstrelsy, bush ballads), they were also attracted because country songs are story songs, and in traditional Aboriginal society this is what songs did too – told stories.”

Adapting the tradition of campfire singing, Aboriginal singers began to make small inroads into the music industry. Jimmy Little began releasing albums in 1956, and his 1963 hit “Royal Telephone” made him the first Aboriginal pop star; he has remained popular ever since. Other prominent country-influenced performers/songwriters from the 1960s and 70s include Bob Randall, Herb Laughton, Lionel Rose, Gus Williams, Auriel Andrew, the Soft Sands band and early rocker Vic Simms. In the 1980s, Roger Knox became the unofficial King of Koori Country, and more recently artists such as Bobby McLeod, Warren H. Williams and June Mills have attracted well-deserved attention. Western Australia’s Broome-based Pigram Brothers (who in a former incarnation were rock band Scrap Metal) continue to release relaxed country-folk albums, and singer Troy Cassar-Daley has achieved enormous commercial success, winning national praise at the annual Country Music Awards in Tamworth NSW – Australia’s version of Nashville.

Reggae Roots

The real revolution in Aboriginal music began in the late 1970s, with the documentary film Wrong Side of the Road. For the first time, the idea of Aboriginal music was seen to encompass a contemporary scene, as well as its purely traditional and country forms. The film showed the Aboriginal rock bands No Fixed Address and Us Mob struggling to get exposure for their reggae-influenced songs. It marked the beginning of a public recognition of music as a tool in the fight to communicate the Aboriginal story. In particular the No Fixed Address song “We Have Survived”, written by the band’s frontman Bart Willoughby, made the point that the Aboriginal people would not simply disappear into the background:

We have survived the white man’s world

And the torment and the horror of it all

We have survived the white man’s world

And you know, you can’t change that!

Bob Marley, who toured Australia in 1979, had a marked influence in the early days of this Aboriginal contemporary music scene. As throughout Africa, Marley’s socially conscious music, with its “Get Up, Stand Up” assertions, had a strong resonance and a number of Aboriginal-based bands began using reggae and rock formats to express their connections with the other black peoples of the world.

The Rock Circuit

The number of Aboriginal rock bands formed over the past three decades is phenomenal, on a scale similar to that of the punk explosion in Britain or the US, and more lasting. Even in the sparsely populated Northern Territory, virtually every remote community has its own band.

The two most notable bands of the 1980s were Warumpi Band and Coloured Stone. The desert-bred Warumpis attracted attention as the first mixed Aboriginal and white band, singing in both tribal languages and English. Fronted by the late George Rrurrambu, their flamboyant lead singer, and white songwriter/guitarist Neil Murray, Warumpi’s 1983 single “Jailanguru Pakarnu” (Out from Jail) was the first rock song ever recorded in an Aboriginal language. Their 1984 debut album Big Name, No Blanketscontained the singles “Blackfella/Whitefella”, “Breadline” and “Fitzroy Crossing”, which all received national radio airplay. They followed up with Go Bush in 1987, which included the iconic song “My Island Home”. Their next album, Too Much Humbug, didn’t appear until 1996, and the band officially retired in 2000, though Murray continues to pursue a creative solo career.

Coloured Stone, led by Buna Lawrie, originated in South Australia in 1978 and was one of Australia’s longest-lasting indigenous bands. Their mid-1980s albums Kooniba Rock, Island of Greed and Human Love caught the ear of mainstream radio with the catchy singles “Black Boy” and “Dancing in the Moonlight”. Lawrie continues to perform with his latest group The Peace Tribe.

Since 1990 there has been continuous development within the indigenous rock/reggae scene, with most new bands coming from the regions around Darwin, Alice Springs and Aboriginal-controlled Arnhem Land. While many have only been locally popular, others have gone on to record and undertake major tours. The most prominent groups have been Mixed Relations, Blek Bala Mujik, Letterstick Band, Sunrize Band and Lajamanu Teenage Band. Current Arnhem Land favourites include Nabarlek, Saltwater Band and Yilila.

Yothu Yindi

Yothu Yindi (“Mother Child”) have been far and away the most successful exponents of distinctively Aboriginal rock, both at home and abroad, and are inseparably associated with the struggle for Aboriginal rights. Former schoolteacher Mandawuy Yunupingu and his fellow band-member Witiyana Marika are sons of leaders of the Gumatj and Rirratjingu clans in Northeast Arnhem Land.

Yothu Yindi’s first album, Homeland Movement, was released in 1988, Australia’s bicentennial year – an event which provided a focus for their protest. Their second release, Tribal Voice (1991), spawned the massive hit single “Treaty”, which has become an Aboriginal anthem.

In concert, the band has continued to address social injustice as well as the wish for harmony and reconciliation between black and white. The band itself symbolizes this, with its mix of Aboriginal and white (balanda) musicians, and Western and indigenous instruments (clapsticks and didgeridoo). Yunupingu was declared “Australian of the Year” in 1992 for his work in promoting Aboriginal culture and inter-racial harmony.

While no longer the musical force that they once were, Yothu Yindi still offer a unique live experience, with their body-painted dancers and a repertoire that includes arrangements of traditional and sacred songs, giving a strong spiritual dimension to their music.

Singer-songwriters

Perhaps the most important development in Aboriginal music over the last thirty years has been the emergence of a number of individual singer-songwriters. Able to eloquently express themselves by sharing their often traumatic life-experiences, their personal perspectives have acted as a bridge between cultures, and educated many listeners about Australia’s history.

Assimilation was the euphemistic term for a policy, practised up until the 1960s, of taking children from their parents and raising them in white foster homes or institutions. Many of these children, some of mixed race, were literally kidnapped and told that their parents were dead. The institution responsible was called the “Aborigines Protection Board” – an astonishing piece of doublethink. The theory was that children reared away from traditional influences would choose to become like whites. In fact, a good many children felt compelled to try and track down their families and rediscover their roots.

Three of them – Kev Carmody, Archie Roach and his wife Ruby Hunter – have become major singer-songwriters, and are today among the most powerful indigenous voices of Australia.

Kev Carmody

Kev Carmody, who was taken from his family when he was ten, has become the leading balladeer of Aboriginal concerns and has been dubbed Australia’s Dylan. The angry, insightful lyrics of his 1990 album Pillars of Society were informed by his doctoral research into the white treatment of Aborigines. He is especially contemptuous of the hypocrisy of British colonizers, a theme brilliantly developed in the song “Thou Shalt Not Steal”:

1789 down Sydney Cove the first boat people land

And they said sorry boys our gain’s your loss we’re gonna steal your land

And if you break our new British laws you’re sure gonna hang

Or work your life like our convicts with a chain on your neck and hands

They taught us Oh black woman thou shalt not steal

Hey black man thou shalt not steal

We’re gonna change your black barbaric lives and teach you how to kneel

But your history couldn’t hide the genocide, the hypocrisy was real

’Cause your Jesus said you’re supposed to give the oppressed a better deal

We say to you yes our land thou shalt not steal, Oh our land you better heal

Carmody’s subsequent albums have sustained his strong vocal style with hard-strummed guitar and occasional didgeridoo, and his 1993 duet with Australian troubadour Paul Kelly, “From Little Things, Big Things Grow”, remains a much-loved national classic. His influential voice has found a wide audience, notably in schools.

Archie Roach was taken from his parents at the age of three and told that his family had perished in a fire. As a teenager he discovered that his mother had died only recently, and the shock was devastating. Dispossessed and rootless, like thousands of Aborigines he resorted to drink and spent the next ten years in an alcoholic haze. “I went from city to city, living on hand-outs. Playing music was my way of getting money to drink. Finally I stopped drinking and music seemed the natural thing to fill up the void. It was therapeutic. Still is.”

Roach’s expressive songs, often simply written for voice and guitar, sound confessional and many come directly from his own experience. “Took the Children Away” made his name and appeared on his 1990 debut album, Charcoal Lane:

Told us what to do and say

Told us all the white man’s ways

Then they split us up again

And gave us gifts to ease the pain

Sent us off to foster homes

As we grew up we felt alone

Cause we were acting white

Yet feeling black

The recognition that some of the evils committed against Aboriginal people are at last being overturned was an important theme in Roach’s second album, Jamu Dreaming. The title track celebrated the rediscovery of lost ancestral values by urban-dwelling Aborigines. His more recent albums, Looking for Butter Boy and Sensual Being, share the recurring twin themes of hurt and hope.

Roach’s wife Ruby Hunter pursues a solo career, as well as performing alongside her husband. With her deep husky voice and folk style, Hunter offers unique insights from the perspective of an older Aboriginal woman – especially noteworthy given the silence that Aboriginal women can be bound to in traditional contexts. Her 1994 debut album Thoughts Within, its follow-up Feeling Good (2000) and the stage presentation Ruby (2005) have all served to solidify her reputation as Australia’s most articulate indigenous female voice.

The rise of female Aboriginal performers has greatly broadened the perspective of Australian indigenous music. The vocal trio Tiddas (“Sisters”) enjoyed a popular decade-long career of close harmonies before disbanding in 2000, and the Stiff Gins currently occupy similar musical territory. Singer-songwriters Kerrianne Cox, Lou Bennett, Shellie Morris and Emma Donovan have all found enthusiastic audiences for their work, and Emma’s cousin Casey Donovan won the 2004 Australian Idol TV programme.

Other notable male singer-songwriters who have emerged in recent years include Frank Yamma, Dan Sultan, L.J. Hill and actor/musician Tom E. Lewis. However, the most recent indigenous success story has been the phenomenal rise of Elcho Island singer and guitarist Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu. Blind from birth, Yunupingu first came to prominence in his cousin Mandawuy’s band Yothu Yindi, and then went on to form his own Top End group, the Saltwater Band. But it was his 2008 solo album Gurrumul, featuring Yunupingu’s remarkably pure and gentle voice in an acoustic setting, that has propelled him to the forefront of the Australian indigenous music scene, and made him a household name across the country. Praised by one music journalist as “the greatest voice this continent has ever recorded”, Gurrumul won two ARIA Awards (the Australian Grammys) for Best World Music Album and Best Independent Release.

The Torres Strait Connection

The Torres Strait archipelago is made up of over a hundred islands. Its first inhabitants are believed to have migrated from Indonesia thousands of years ago, when there was still a land bridge between New Guinea and Australia.

The discovery of pearl shell in the 1860s led to an influx of people from all over the Asia/Pacific region, concentrating on Thursday Island. The colony of Queensland officially annexed the islands in 1879, but they have maintained their own distinct culture and identity, with strong links to both the mainland Aboriginal people and the tribal groups of New Guinea.

The Mills Sisters – Rita, Cessa and Ina – formed in 1970, and performed their traditional island songs around the world. Perfectly summing up the relaxed Torres Strait Islander lifestyle, these swinging island grannies’ 1993 album Frangipani Land still makes for essential listening. Rita began performing solo in 1995, and died in 2004.

Without a doubt, the best-known Torres Strait Islander performer is singer/dancer/actor Christine Anu, who brought a youthful pop sensibility to her first single, “Monkey & the Turtle” (1994). Her 1995 remake of Neil Murray’s Warumpi ode “Island Home” has remained her signature tune ever since:

I come from the saltwater people

We always lived by the sea

Now I’m down here living in the city

With my man and my family

My Island home/my island home

My island home is waiting for me

Anu has remained in the public eye with her follow-up albums Come My Way (2000), 45 Degrees (2003) and the live set Acoustically (2005). She’s also pursued an acting career.

A favourite Torres Strait Islander performer at present – both at home and on the mainland – is septuagenarian crooner Seaman Dan. Other notable musicians include King Kadu (Richard Idagi), storyteller Getano Bann and local Thursday Island band Totemic.

Here Come the Hip-Hoppers

Like young people all over the world, in recent years many young Aborigines have been attracted to hip-hop. Adapted to their own culture and environment, hip-hop has encouraged a whole new generation of indigenous Australian musicians to come forward. While some of the beats, hand-gestures and baseball caps may be borrowed from abroad, there’s no denying that Aboriginal hip-hop is establishing its own distinct style.

Whether it’s the urban wordplay of inner-city rappers like Wire MC, Local Knowledge and Radical Son, the hardcore sound of Central Desert rockers NoKTuRNL or the sassy raps of female Arnhem Land crew Wildflower, indigenous hip-hop seems here to stay. While many young Aboriginal hip-hop artists are yet to properly record their work, every year sees a few more releases, and the live scene is booming.

Blackfella/Whitefella

Over the years there have been numerous musical partnerships between black and white Australian musicians. While Yothu Yindi and Warumpi Band are the best-known examples, a couple of others deserve special mention. Inspired by renowned Aboriginal actor David Gulpilil, the band Waak Waak Jungi is an occasional collaboration between Arnhem Land songmen and rurally based white musicians from Victoria. Their 1997 album Crow Fire Music was a successful blend of traditional vocals and ambient soundscapes. Warren H. Williams has regularly collaborated with fellow Aussie country star John Williamson, and their musical partnership yielded the classic 1998 hit single “Raining on the Rock”. The 2001 album Corroboration: a Journey through the Musical Landscape of 21st Century Australia featured collaborations between an all-star cast of indigenous and non-indigenous pop performers.

The careers of several other white Australian musicians have been closely associated with indigenous issues. Among them are ex-Warumpi singer-songwriter Neil Murray, Goanna band founder Shane Howard, Gondwanaland’s didge virtuoso Charlie McMahon, and veteran rock band Midnight Oil. Singer/keyboardist David Bridie has produced a number of albums for Aboriginal artists, and with his own band Not Drowning, Waving he has forged ties with indigenous musicians from Papua New Guinea and West Papua. In 2008, a mixed-race, all-star indigenous group – the Black Arm Band – emerged, featuring some of Australia’s finest musicians. Fronted by Archie Roach and Shane Howard, this large group has appeared at major festivals in both Australia and the UK, and a stripped-down version of the ensemble, Liyarn Ngarn (“the coming together of the spirit”) has also toured extensively.

Australia’s World Music Scene

Multicultural Australia has also become the adopted home for a substantial number of first- and second-generation migrant musicians from around the world. The result has been a vibrant local world-music scene in most of the major cities, with urban venues regularly presenting African, Asian, European, South American and other acts. Adelaide has hosted Australia’s annual WOMAD Festival since 1992, and many of the country’s other regional festivals often contain a strong world music component.

Drum Drum (Jak Kilby)

Currently prominent non-indigenous acts include Australian/Kazakh guitarist Slava Grigoryan, Tatar/Russian singer Zulya, cheesy gypsy band Monsieur Camembert, the Eastern European-influenced group Mara!, soulful Tongan sisters Vika & Linda, Papuan troupe Drum Drum, female acapella quartet Blindman’s Holiday, Australian/Egyptian oud player Joseph Tawadros and multi-ethnic party band The Cat Empire.