Monday, March 1, 2021

A Beginner's Guide to Habib Koité

By Daniel Brown

The Malian singer-songwriter Habib Koité is also one of his country’s leading guitarists. Daniel Brown reflects on the artist’s recordings and career to date

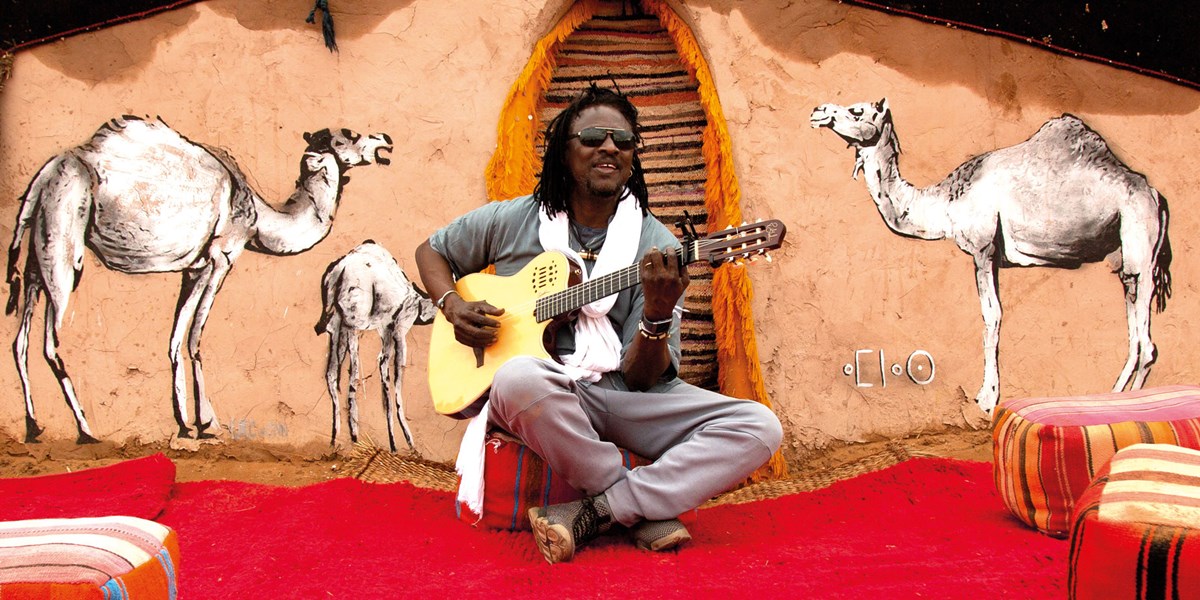

Habib Koité (photo: Margot Canton Lamousse)

Should you cross Habib Koité wearing a furrowed brow, ambulating through his ten acre field, 25km from his home/studio/refuge in west Bamako, he’s probably working on a new album. With giant strides, he paces back and forth before returning to his iPad and Godin guitar, resting up on one of the rare trees giving shade under a burning Malian sun. He’ll grab his iPhone to listen to the melodic line he just composed and re-record another version. Habib’s creative juices might be in full flow, but it’s no cakewalk. “You can’t imagine the pressure and stress I put myself under when there’s a deadline for a new album. I’ll isolate myself for days, blocking out everything and think of nothing else until it’s over. It’s torture.”

Which might go to explain why one of Mali’s foremost guitarists has only released six solo albums in his 26-year international career. Each one is a carefully crafted product of Habib’s quest for the perfect marriage between his different influences. “Composing is a terrible process for me, it explains all the white hair I have,” he says in a long, rambling but fascinating exchange that lasts over five hours. The 62-year-old is on a mission of transmission, encapsulated by his latest album Kharifa.

“Kharifa means ‘what you’ve been confided with’,” he explains. “It’s so we don’t lose what’s been handed down. Over my 40-year career, I’ve always been aware of this legacy, my inheritance from a family of griots. In posterity, I hope I can be considered a link joining two chains, a ring that attaches the traditions from my Khassonké Mandinka culture to the multitude of others – both in Mali and abroad – that I’ve picked up.”

Music always coursed through Habib’s family home in Kayes, the same western Malian city that gave us Boubacar ‘Kar Kar’ Traoré and L’Orchestre Sidi Yassa. His grandfather played the djeli ngoni, his father plucked the banjo during his time off as a railwayman, his griot mother sang, as did his sisters. “And there were always guitars lying around the house, which my brothers strummed while sipping tea. It didn’t take long for me to mimic them.”

Habib Koité went one giant step further than his 17 siblings. In 1977, he was accepted by Bamako’s Institut National des Arts where he discovered the entirely new world of classical guitar playing. But it was the 1978 meeting there with Kalilou Traoré, elder brother of ‘Kar Kar’, that proved decisive. “As a teacher, he showed me another world,” says Habib. “He’d spent eight years in Cuba, was one of the founders of Las Maravillas de Mali and he gave me the keys, which opened up the world.” Habib graduated with brio and quickly began playing alongside the likes of Toumani Diabaté and Kélétigui Diabaté (who later joined Habib’s band). Then, in 1988, he formed his five-piece group, Bamada.

The live scene has since engulfed the artist, dubbed a ‘road warrior,’ as the guitarist has clocked up over 2,000 concerts worldwide. Yet, it is the wealth of Mali’s musical cultures that continues to intrigue him. “People don’t realise just how important and diverse it still is,” he says, warming to the subject. “There are so many scales, instruments… and cultural values! We sing about everything, peace, society, marriage, birth, history. It reflects the intelligence of these populations, it’s a school teaching us thought-out social rules which create well-distributed communities.”

Habib spent months studying these styles, watching how the Bobo hunters rested their palms on the guitar bridge, or the different ways the Bamana and Mandinka tune their guitars. He then spent as much time working them into his own compositions. ‘I wanted to link the micro-cultures of Mali through me as if I were a nucleus and from me many rays leave,’ he told Angel Romero from worldmusiccentral.org last year.

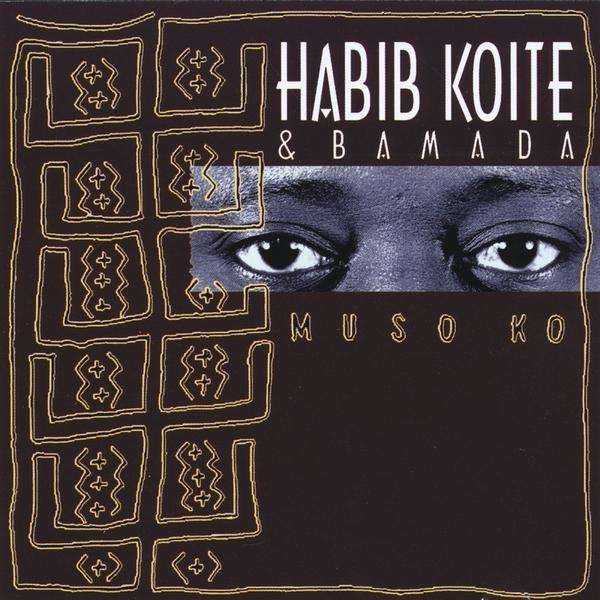

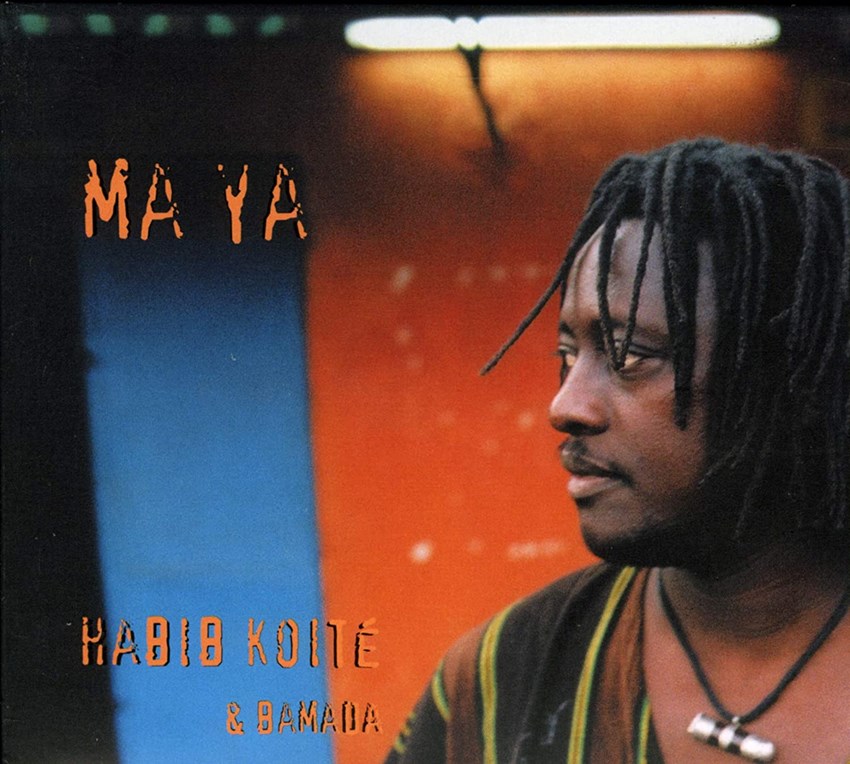

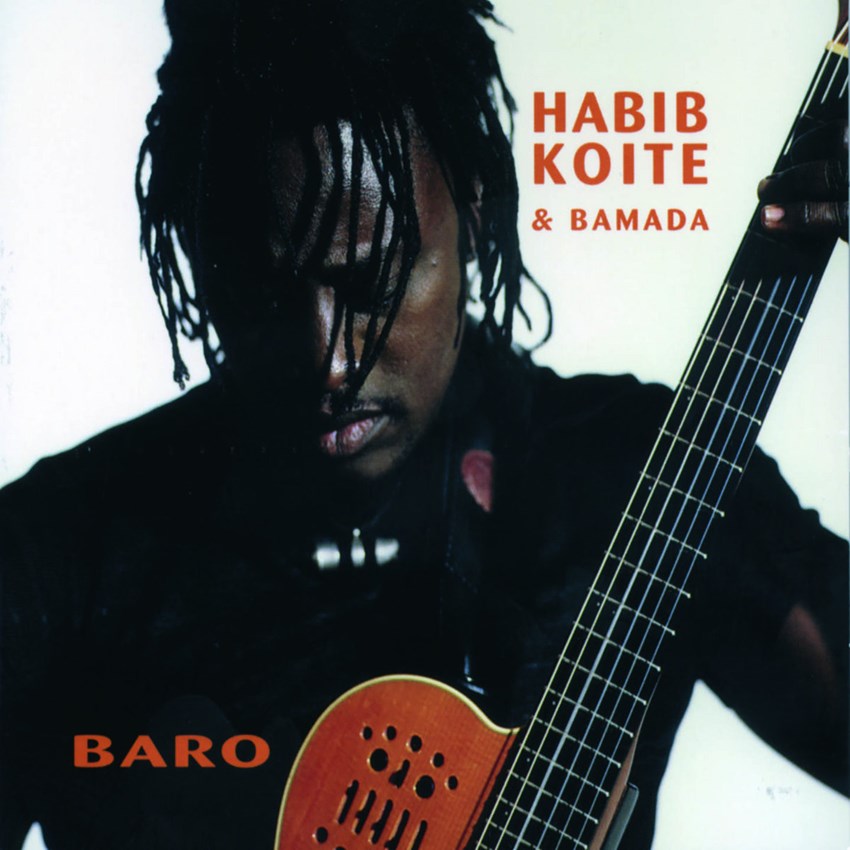

Each one of Habib’s albums is faithful to these explorations. His first in 1995, Muso Ko, distils years of live performances in which his guitar resonates like a ngoni. His follow-up, Ma Ya, softens the Songhai’s Takamba rhythms and reshapes them into bluesy and soulful excursions through diverse Malian musical communities. In the 2001 album, Baro, you can hear the tama (talking drum) converse with Habib’s Godin guitar. His fourth, Afriki (2007), sees the composer invite antelope buru horn players from Ségou to underscore ‘Nta Dima’ and resonate through his lyrics against fixed marriages. The 2014 album Soô mixes the Khassonké danssa doso rhythms with a guitar that Habib tunes to a pentatonic scale mirroring the strings of the kamalengoni. Finally, his 2019 album, Kharifa, resonates throughout with Mali’s emblematic instruments (the dunun drum, ngoni, flute, kora…), as Habib tests his linguistic dexterity with the Dogon language in ‘Mandé’. Once again, he reaches out to the youth, including his two musical sons, to show them that ‘tradition’ can still cohabitate with ‘fashionable.’ “The youth forget their own belly button, they turn to foreign sounds,” he exclaims. “I try to show them that our sounds are so varied, reach an inexhaustible source of riches. We seek a paradise abroad and forget that it’s here, at home!”

However, Habib in no way confines himself to Mali’s borders. His enduring partnership with Michel de Bock, director of the Contre-Jour label and production company, which began back in 1994, helped him reach out to dozens of fellow musicians. The meetings have given birth to collaborations with the likes of Vusi Mahlasela, Eric Bibb, Bonnie Raitt, Dobet Gnahoré, Jackson Browne and many more. The friendship with the latter has truly blossomed since Browne invited Habib to join in his Artists for Peace and Justice project bringing together artists from Haiti, Mali, the US and Spain. “The album we made together is ready for release, we want to take it live, but this cursed COVID-19 health and economic crisis has pushed back its promotion and concerts.”

Indeed, Habib cannot hide his concerns over the joint impact of the pandemic and Mali’s embroiled political crisis. “I’ve never known such difficult moments. We’d worked so hard on preparing a 34-concert tour in 2020 to showcase Kharifa, only to have it all wiped out by serial cancellations. At the same time, curfews, blockades and political tensions here in Bamako are pushing even established musicians like myself to despair. It’s unprecedented.”

At present, this gentle giant of West African music is digging deep into his reserves to keep afloat. It is, he says, a moment to take stock, to reflect on past victories and ponder on future creations. Habib Koité retains a strength behind the gentleness of his voice and guitar-plucking. For, as the Bamana saying goes, ‘God gives nothing to those who keep their arms crossed.’ As those who have witnessed Habib live, this is a man who is not known to cross his arms, nor is he likely to do so during the turmoil his country is traversing.

BEST ALBUMS

Habib Koité & Bamada

Muso Ko (Contre-Jour, 1995)

Muso Ko is Habib’s debut release, an 11-track album that shot up to the top of the European World Music Charts. It features Habib’s anti-smoking hit ‘Cigarette a Bana’, and was re-released in the US in 1999.

Ma Ya (Contre-Jour, 1998)

An album that consolidated Habib’s reputation as one of West Africa’s most promising talents. More intimate and reflective, it sold over 100,000 units worldwide.

Baro (Contre-Jour, 2001)

Habib injected Latin rhythms and melodies in this commercially-driven album. But Baro never leaves Habib’s Mandinka soul far behind.

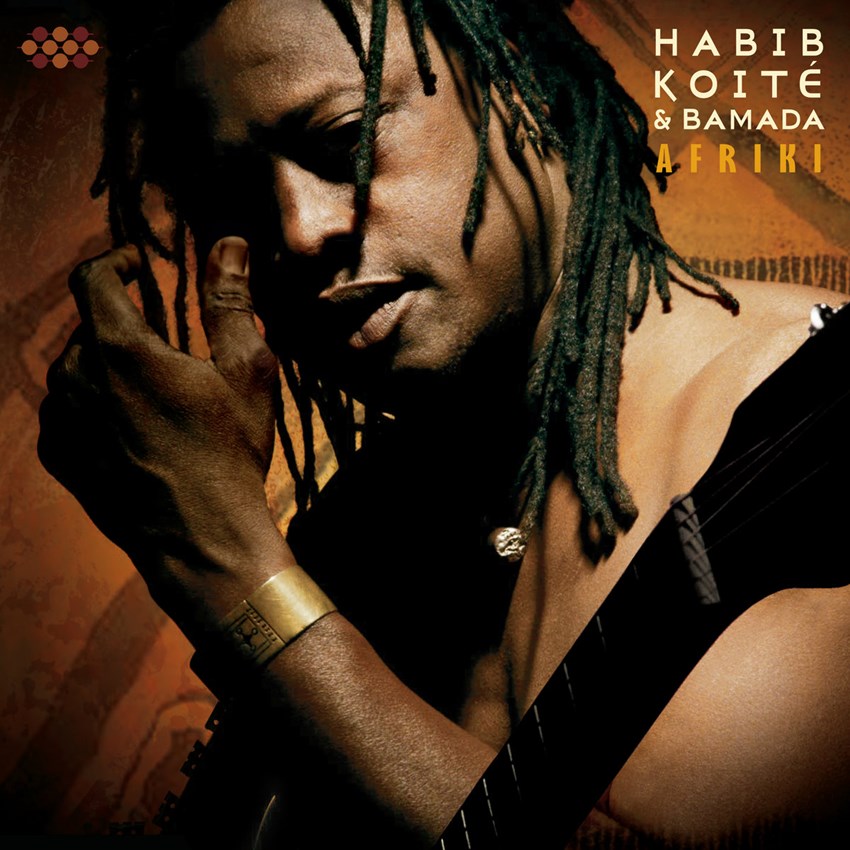

Afriki (Contre-Jour/Cumbancha, 2004)

The crooner opens his repertoire further to incorporate Tamashek songs from Timbuktu, Wassoulou hunting tunes and Bamana melodies from Ségou. Many are peppered by the reggae rhythms that were gaining ground in Bamako. A Top of the World review in #47.

Eric Bibb & Habib Koité

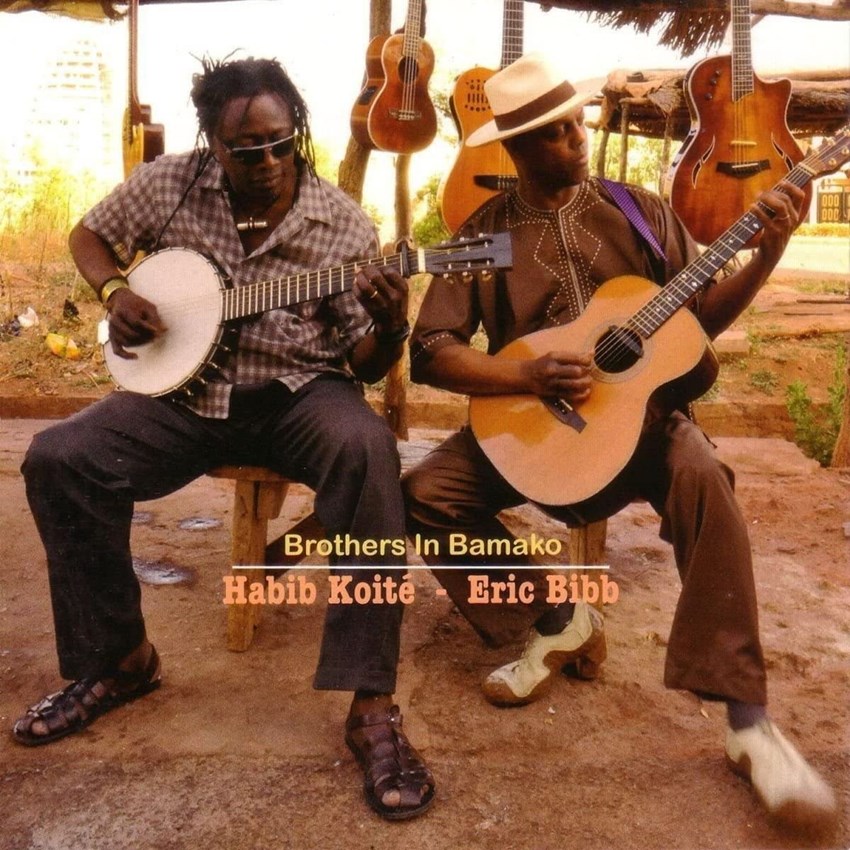

Brothers in Bamako (Contre-Jour/Dixiefrog, 2012)

A sumptuous meeting of guitars and voices with American bluesman Eric Bibb. Ten years after crossing paths for Putumayo’s Mali to Memphis compilation, the two master musicians prove that common roots can forge acoustic bridges across time. Reviewed in #89.

This article originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of Songlines magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!