Friday, July 19, 2024

Ballaké Sissoko and Derek Gripper: “We’re happy to disrupt”

By Emma Rycroft

Kora music gets a radical reworking with Ballaké Sissoko welcoming South African guitarist Derek Gripper into the tradition

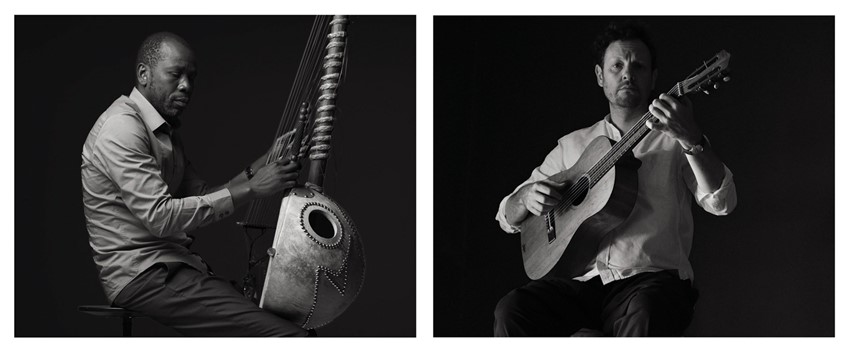

Ballaké Sissoko and Derek Gripper (photo: Eyüp Berk Kılıç)

Ballaké Sissoko and Derek Gripper’s self-titled album opens with ‘Ninkoy’, a conversation between their respective kora and guitar. Hesitant at first, each gives space for the other. Soon though, the strings are dancing, rendering the same motif, albeit distinctly, in tandem. The kora ripples, then is plucked; the guitar stays steady and low before Gripper breaks out into a new melodic path that the kora follows. It sets the tone for an album that marks a fresh step not only for the musicians involved but for their respective traditions, too.

Ballaké grew up in the Mande/kora tradition as part of a griot family. His Casamance heritage and musicianship were, in fact, recently laid out in the moving documentary Kora Tales. And he’s entwined in the international history of kora music, too. His father featured on the first major kora album, Sidiki Diabaté & Djelimady Sissoko’s Cordes Anciennes (Ancient Strings) (1970), and Ballaké paired up with Toumani Diabaté for the hugely successful filial follow-up, Nouvelles Cordes Anciennes (New Ancient Strings) (1999). South African Gripper, on the other hand, was initially somewhat of an outsider to this world, growing up and studying classical guitar in South Africa. He fell in love with the kora, however, after university. In 2011, after much studying of the instrument and its repertoire, he transcribed music from Toumani and Ballaké for guitar and released the album One Night to Learn. Garnering huge acclaim for this boundary-stretching work, he toured it for several years before releasing another kora-based record, Libraries on Fire, in 2016.

Ballaké Sissoko and Derek Gripper (photos: B Peverelli & Simon Atwell)

Lucy Durán, professor of music at SOAS and co-director of Kora Tales, has praised the coming together of these two musicians and instruments: “It’s the furthest away that Ballaké has gone from his own idiom and it’s brilliant – not world music, it’s in a totally different realm, entering new territory.” Ballaké agrees. “It’s not even a project,” he tells me from his home in Bamako, “For me, it’s an adventure… It’s an adventure that has a continuity. It’s not that it stops here. No. I see this from a very, very far distance. It can really be shared by generations.”

It’s something that excites Gripper, too. When I talk to him, he’s in New York readying for a trip to South Africa where he will meet Ballaké for a tour around that country (which Ballaké is visiting for the first time). “We’ve taken half of the duo out of the kora onto [guitar]. So now we’re not exploring the lyricism [of two koras] as much, we’re exploring tonality and movement and change more. So, I think there’s a nice musical progression.”

Ballaké Sissoko & Derek Gripper was recorded after Ballaké and Gripper had performed only twice together, in Paris and London. During their time in the UK for the latter show, the pair went to Platoon’s studio and improvised for just under three hours. “I left [it] on my hard drive for six months,” says Gripper. He feared the music would disappoint him. “And then I finally plucked up the courage… I pressed play and the first track is a 16-minute improvisation around a piece of mine called ‘Koortjie’, which became one of the tracks on the album. Luckily, that one is the best full improvisation. How, I don’t know… I was really just blown away. I actually kind of cried when I heard it… It took me then another few months to listen to the rest because I just didn’t want to hear it and know that it wasn’t going to be as good as that. This is the music that I’ve always wanted to make.”

Gripper cut the improvisations into smaller pieces and managed to shape the record. With help from record label Matsuli, it was pressed and released physically and digitally. ‘Koortjie’ itself is a jaunty, delicate track, containing some distinctly South African motifs. A handful of notes from each instrument rhythmically build pace one against the other before the wave of energy crashes and they start back more slowly, circling that rhythmic motif to escalate again before it develops into a more rippling theme. ‘Moss on the Mountain’, by contrast, begins with a thunderous stir from the deep tones of guitar, with kora above it, before the two separate out slightly. It’s a tune with depth and turmoil to it, the guitar tending to provide a low background for the characteristic undulations and pirouetting notes of the kora. The emotion of each track, however, is manifold and seems to vary on each listen, perhaps because of its inherent transience as improvisation. “It’s kind of difficult to hold in your mind,” muses Gripper. For Ballaké, “You have to take time to listen to it and understand the reaction… The point is that we express ourselves, try to know each other one with the other.”

Listening and expression, perhaps predictably, are central to the creation and enjoyment of the pair’s improvisation. “We’re not looking for, you know, the next clever musical idea,” explains Gripper, “We’re just listening to one thing. And then it suggests something and then you do that and then you get bored and you just go somewhere else… But every time we’re somewhere, you sit there with it for a while… kora music is really conducive to that. There’s always these places where you can just sit and rest on this cycle and then you realise, ‘Oh yeah, that note, oh I wasn’t listening to that,’ and then you change it… and then it goes. So it’s designed for that, for really being able to listen, as opposed to, you know, a piece of Bach, which can feel like you’re on a freight train.”

In between and following the recorded work, the duo have been touring extensively. Their performances, however, continue with new improvisation rather than looking back at that which has already been set down. “When I finally got the record,” says Gripper, “I thought, ‘wow, it would be interesting to learn those pieces now,’ and then I realised on tour that we were never going to do that.” The theme of expansion crops up again: the pair share a love of stretching boundaries and exploring that simply doesn’t allow them to stick to one repertoire. “We’re more going on these structural journeys,” is how Gripper explains it, “and if Ballaké wasn’t into that or able to engage with that, it wouldn’t work… But he enjoys that. And when he improvises by himself, he does that. He plays ‘Miniyamba’ for a few seconds and then he just flips and suddenly he’s somewhere else. He doesn’t feel that he needs to stick around for ages in some place just because he’s there. He just lets it change and we share that, the fact that we’re happy to disrupt.”

As well as exploring possibilities, this improvisation revolves around connecting to a moment in time and space. “We try to share with the place,” says Ballaké, “Even if we play in a house where there is no one, it’s the quality of the house that can inspire us. Even when we do concerts, even if we do a hundred concerts, [that inspiration] will not [produce] the same thing.”

Ballaké and Gripper have no shared language outside of their music, using Google Translate for most of their interactions. But there is an abundant warmth in the way each connects with and talks about the other. The magic of the record is far from falsified. I ask Ballaké about the difficulties of developing a relationship without a spoken language, “On the face of it, it is difficult,” he tells me, “But it is not difficult. If you like someone, you see, you’re going to understand them immediately… you do everything to understand them.” For Derek, “Ballaké represents, and I admit this can be total projection, but he represents for me very much the pure act of making music … he doesn’t get in the way of the music and so it just flows out of him… And the results are there to hear in every note.”

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2024 issue of Songlines. Never miss an issue – subscribe today