Thursday, January 31, 2019

Dudu Tassa: An Iraqi Revival

The songs of the Jewish-Arabic band the Al-Kuwaiti Brothers were much loved across the Arab world. Robin Denselow speaks to Dudu Tassa, the grandson of Daoud Al-Kuwaiti, about reviving these songs

Dudu Tassa is an Israeli rock star, songwriter, composer and actor who has turned folk-rock revivalist with an intriguing project. He has set out to rework and re-popularise the music of his grandfather Daoud Al-Kuwaiti, “an amazing singer,” and Daoud’s brother Saleh, a fiddle-player and prolific songwriter, who transformed the music scene in Iraq between the 1930s and 50s, becoming massively popular across the Arab world, before their careers suddenly collapsed.

It’s a story that involves politics, history and some excellent music. Tassa may have set out to explore his family’s history, but in the process he has launched a band, the Kuwaitis, who could well become a global success. They have already toured the US with Radiohead and are planning their first UK shows.

I meet Tassa in a Paris hotel, where he is joined by his co-producer and band member Nir Maimon, and manager Or Davidson, who both step in to translate when he veers from English into Hebrew. They are in Europe promoting the band’s third album, El Hajar, the first to be released outside Israel on CD and vinyl. Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaitis (2011) and Ala Shawati (2015) have so far only had a worldwide digital release.

Dudu Tassa & The Kuwaitis

Like those earlier sets, El Hajar consists of songs originally made famous by Daoud and Saleh Al-Kuwaiti, but are now beefed up by Tassa’s guitar, bass and banjo, Nir Maimon’s bass, keyboards and programming, and the occasional addition of ney (flute), qanun or violin. The songs are, of course, all in Arabic, and Tassa is joined on vocals by female singers, including the excellent Rehela. The best tracks, like the sturdy and melodic ‘Bint El Moshab’, remind me of the late, brilliant Rachid Taha, and the way that he updated popular Algerian songs on his two Diwân albums. Another outstanding track, ‘Ahibbek’, includes samples of original recordings featuring Daoud Al-Kuwaiti on vocals and Saleh Al-Kuwaiti on the kamancheh (spike fiddle).

So how did these two brothers achieve such extraordinary success in Iraq? As Tassa explains, it’s a colourful story. Daoud and Saleh were from a Jewish Kuwaiti family and as teenagers, back in the 1920s, they moved with their parents to Baghdad. One of their uncles had given Daoud an oud and Saleh a violin, and they began playing together and writing new songs, with such success that they became celebrities in the Iraqi capital. Saleh was the composer and lyricist, and according to Tassa he “invented new maqams (the melodic modes used in Arabic music) and according to an Iraqi TV programme we saw, he became the inventor of modern Iraqi music.”

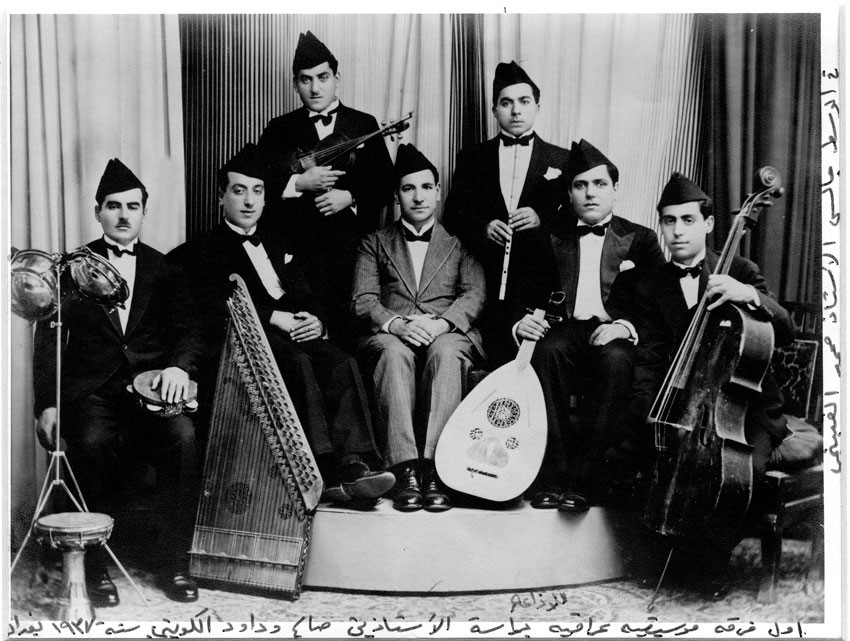

The Al-Kuwaiti brothers’ band

The songs brought the brothers fame and wealth in Baghdad. Tassa says they “played in clubs, stadiums and palaces,” and they even owned a radio station “because the King loved them and gave them the permission and money to do this.” The cover of the first Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaitis album shows Daoud and Saleh surrounded by the Baghdad radio station band, complete with ney and qanun players.

The Al-Kuwaiti brothers’ songs were released in Baghdad on cassette and vinyl, and their fame spread across the Arab world. When the legendary Egyptian singer Oum Kalthoum visited Baghdad in the 30s, she insisted on meeting them, and in return Saleh wrote a song for her. At that time, it seemed that no one cared that he and his brother were Jewish. They were admired and loved as brilliant musicians who sang powerful new songs in Arabic.

But by the 1950s, the mood had changed. Growing anti-Jewish hostility in Iraq intensified after the creation of Israel in 1948, and the Arab-Israeli war that followed. And as violence against Iraqi Jews increased, the vast majority decided to leave – including Daoud and Saleh, who joined the mass exodus of 1951, when Israel organised an airlift. Though according to Tassa “there’s a story that the king sent a messenger to the plane, asking Saleh not to leave Baghdad.”

Life in their new home of Israel was not as easy as they had expected. They had been wealthy, “owning clubs and jewellery,” in Iraq, but were not allowed to take money with them. They expected to be treated as celebrities, but instead they found that few people wanted to hear Arabic song, which was regarded as “the language of the enemy – so they had a big problem with their culture and music. They were embarrassed to speak in Arabic.”

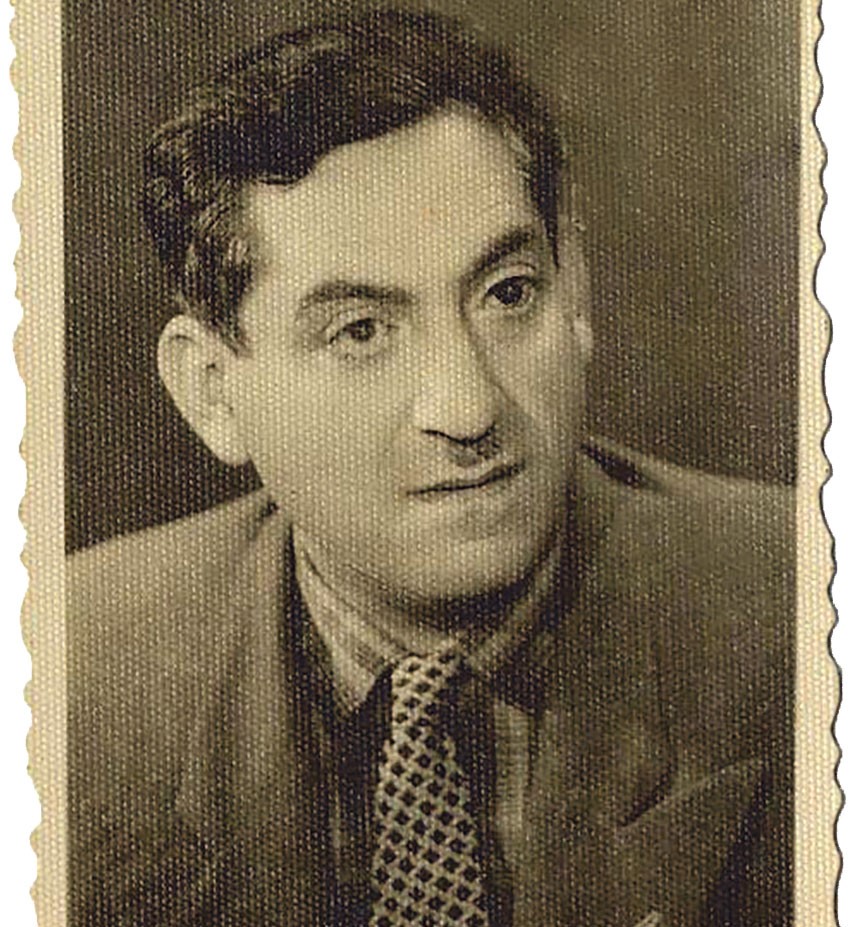

Saleh Al-Kuwaiti

The brothers were still just in their 40s, but their success was suddenly over. “They still played for other Iraqi Jews at weddings or bar mitzvahs, but only small events,” says Tassa. “But Saleh kept writing a lot of songs – many of them about immigration and how he missed Baghdad.” The cover of the second Kuwaitis album shows the brothers looking dejected after moving from Iraq. Once hailed as celebrities, they now survived by selling kitchen appliances in a market. Israel’s national radio station did eventually acknowledge their importance and offered a weekly hour-long slot, “but on a Friday afternoon, when no one would hear it.”

Back in Iraq meanwhile, their songs remained popular, and continued to be played on the radio. But when Saddam Hussein came to power in 1979 he banned all mention of the composer and singer, as well as any acknowledgement that they were Jewish. “They had a lot of fans, and a lot of soldiers were listening to these two Jewish guys, but Saddam erased their names from all the music, so no one would know they were Jewish. You can’t make a song disappear, but you can make the writer’s name disappear. People knew the songs, but not who wrote them. That was the situation when they died.”

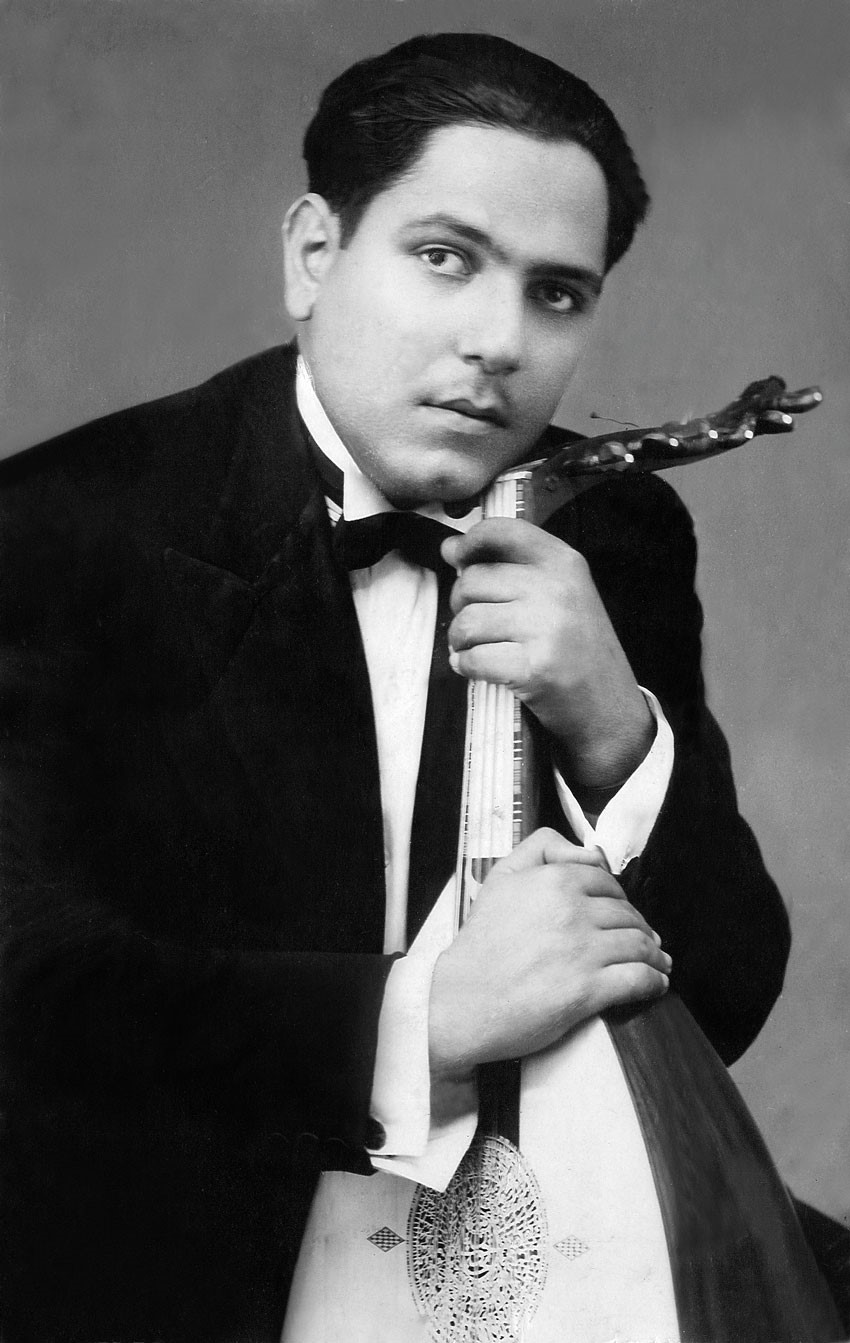

Daoud Al-Kuwaiti

Daoud died in 1977, just a few months before Tassa was born, while Saleh died nine years later. That could have been the end of the story, if his grandson had not decided to investigate and revive the music, and did so despite the fact that his mum – Daoud’s daughter – had tried to stop him becoming a musician – precisely because of the family history. “She said no one will become a singer in our family, because music betrayed us.”

Tassa wisely ignored her, and has enjoyed a lengthy career in Israel. He had his first success at 13, when he was spotted by a record producer when playing in a neighbourhood community band and invited to sing on what would become a best-selling album. He went on to study jazz guitar, work as a session guitarist and write music for films and TV. He released his first solo album, Clearer, when he was 22 and 11 further solo albums have followed, most of them “guitar rock, with just a little taste of Iraq.”

He first became aware of Daoud and Saleh’s music when he heard his mum Carmela singing their songs in the kitchen, “though if a friend came from school it would be embarrassing if she was singing or listening to Arabic music… [It was] only when I was 27 or 28 and had become confident and successful as a rock performer that I started to really have the courage to look at other things,” he says. He began to investigate the Al Kuwaiti brothers’ music, and discovered that not only did his mum still have their cassettes, but they could also be found in an area of Tel Aviv where Iraqi Jews had settled. Together with Saleh’s son, who had written about the music, he went to the radio station to get their recordings of Daoud and Saleh’s sessions in Israel.

He started playing around with the music, sometimes sampling parts of the original recordings and adding chords and harmonies with bass, guitar and electro-percussion, sometimes starting from scratch with his guitar. When he added the Arabic vocals, he asked his mum Carmela to explain what they meant – and then asked her to sing on the album.

His co-producer Nir Maimon says: “I thought he had gone crazy. We made this project basically for ourselves, as an adventure. We had just finished an album that was a great success in Israel and he came up with these weird songs. He said he wanted to do something in Arabic and I said ‘do we need it?’. But that first album sold more in Israel than all the albums in Hebrew – so we were in shock!”

So why had this new fusion style, now inevitably known as Iraq’n’roll, sold so well? Tassa thinks “it came at the right time. People were ready to put aside the whole thing with Arabic.” He put together the Kuwaitis band, which includes qanun, cello and violin, guitar and keyboards, and was delighted to find their “concerts were sold out, with three generations coming – grandfathers, sons and grandsons. The new generation in Tel Aviv are more open-minded – they are open to music from all over. And we didn’t do this as a ‘roots’ project – we went to the cool venues to bring in the hipsters…”

Tassa has continued his solo career as a rock star in Israel, but now always includes Kuwaitis songs in the set. But when he tours abroad, it is with the Kuwaitis band. Their international career kicked off with what he called a “terrible” appearance at the 2011 Babel Med Festival in Marseille, but he has been happier with later shows, which included WOMEX 2016 in Spain. Why not the UK? “Because the market looks very closed from the outside. But now we have PR in England and a company that trusts us, so we will come soon.”

Their biggest concerts to date have been with Radiohead, whom they supported on their 2017 tour of North America, and then in Tel Aviv. Tassa has known Jonny Greenwood, Radiohead’s guitarist, since they met in Israel 12 years ago, and Greenwood played guitar to accompany a Hebrew ballad on one of Tassa’s solo albums. He was delighted by the tour, which included an appearance at the Coachella festival in California, and by the way the Radiohead fans responded to the updated Jewish Iraqi songs. “The Radiohead crowd is very special and open-minded – and they listened, for all the set.”

The careers of Daoud and Saleh Al-Kuwaiti were, of course, transformed by the volatile politics of the Middle East, and politics will inevitably play a role in Dudu Tassa’s international career. Many Western musicians passionately, and understandably, support the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement that calls on artists not to perform in Israel in support for the Palestinian struggle. His friends in Radiohead of course broke that boycott by playing in Tel Aviv, so how does Tassa react to that? “We hear it all the time and can understand both sides. What we like about Radiohead is that they are open-minded. Tom Yorke said ‘no one will tell us how to think.’ We still think in a romantic way that music is like a bridge and music can maybe solve a few problems. Maybe if artists toured Israel and also the other side it might make things better.”

Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaitis have performed in Turkey, and gave what they call “two nice concerts in Jordan. It’s not common for Israeli bands to play there.” He has been invited to Lebanon and even to Syria, and would one day like to go to “Kuwait and Baghdad, to take the music to the place where it was invented. But that’s not possible with Israeli passports.”

The new album by Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaitis, El Hajar, is a Top of the World album in Songlines #145

This article originally appeared in Songlines #144. To find out more about subscribing to Songlines, please visit: Subscribe