Thursday, March 6, 2025

Field of Research: Ewan MacColl

By Allan Moore

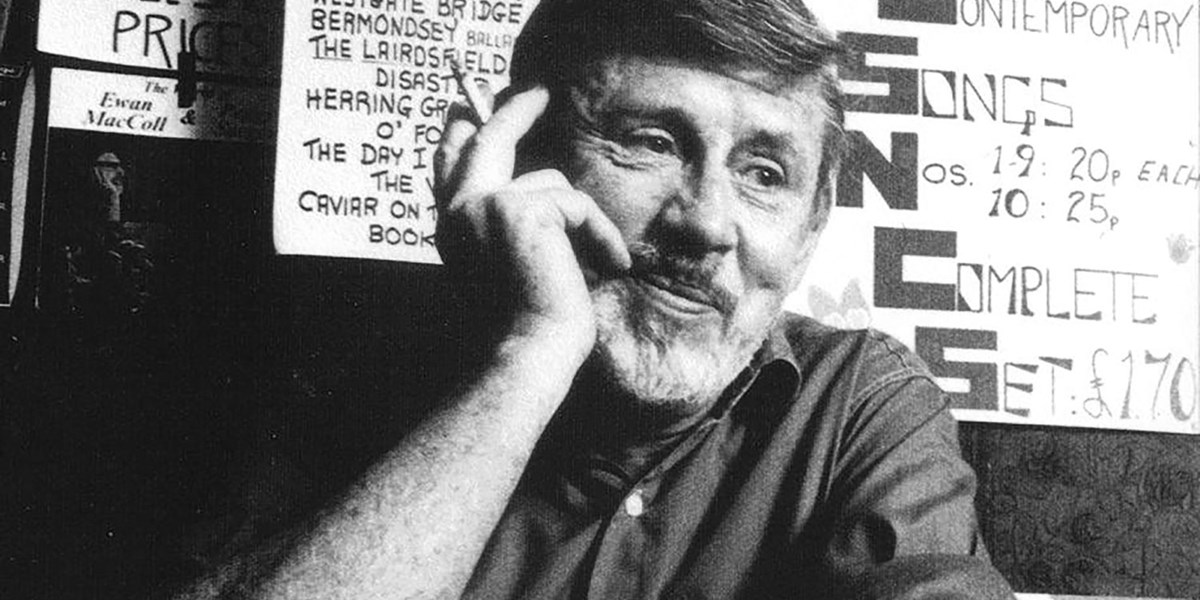

On the 110th anniversary of the legendary folk singer’s birth, Allan Moore looks back at his legacy and skill

Ewan MacColl

Ewan MacColl (stage name of James Miller, 1915-89) provided the spark for the Second English Folk Revival, which ignited in the 1950s and whose embers burn to this day. MacColl was self-taught: an unschooled, voracious reader; a Marxist, organiser and performer; a playwright, actor, songwriter, singer and debater; a literal mover and shaker. An early interest in radical theatre remained with him throughout his life. In 1932, he wrote ‘The Manchester Rambler’, his first significant song, and from the later 1930s, he wrote for the BBC and his then-wife Joan Littlewood’s experimental theatre workshops. One of these birthed his famous ‘Dirty Old Town’ of 1951, while his 1954 collection of industrial songs, Shuttle and Cage, demonstrated the limitations of the pastoralist conception of ‘folk’.

Beginning in 1950, he recorded a series of 78s for Topic, the revival’s major label. Then, at the end of 1956, he and fellow instigator AL Lloyd recorded the first landmark recordings of the Revival, their eight-LP set of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (The Child Ballads), based around the Child collection. In 1953, he had scripted and coordinated a BBC series, Ballads and Blues, utilising Lloyd, the US collector Alan Lomax and jazz trumpeter Humphrey Lyttelton. Five years later, in 1957, with his partner Peggy Seeger and sound recordist Charles Parker, he produced the first of the hour-long Radio Ballads, on conditions for British railway workers. In all, eight such programmes were broadcast by 1964; although of uneven quality, they brought to the radio audience voices of British society generally overlooked (further such programmes were broadcast over the next 50 years).

The programmes’ significant advance was to use ‘real people’ rather than trained actors: they combined an astute mix of reminiscences from individuals with newly composed songs by MacColl and Seeger. Accompanists were generally a combination of Seeger (banjo and guitar), Alf Edwards (concertina) and members of a small jazz band – it’s worth noting that the British Dixieland revival coincided (and sometimes overlapped) with the folk revival. This runs contrary to MacColl’s image as a purist, owing to practices such as those in his own folk club whereby singers would not sing songs from traditions and locations of which they were not inheritors – a ‘policy’ followed by other UK folk session organisers at the time. In his recordings, there was no dominant guitar (for many revivalists, especially in the US, the guitar – both portable and chordal – came to dominate).

A sense of the dramatic underlay all his activities, bringing with it an analytic mindset which made him unusually willing to address practices of performance, his own and others. There is a passage in his autobiography where he comments on the rethinking of ballad singing which he undertook from about 1980, when he became conscious of the singing choices he could make: remarkably, he openly admits here that some of his more instinctive choices of two or more decades earlier were not necessarily successful. In essence, MacColl developed three broad approaches to the singing of a song or ballad, approaches which he continued variably throughout his singing career. These approaches privilege, in turn, metre, rhythm and melodic contour. Metre refers to the regularity of the beat and the pattern of stressed and unstressed beats, the time signature. Rhythm is perhaps most easily described as ‘where the words land’. Melodic contour is the shape of the melody – where it rises and falls, how far and how frequently. This is not to say that all three elements are not present in everything MacColl sang, but their relative dominance changes.

You can hear the dominance of metre on ‘The Sweet Kumadie’. The metre set by accompanist Alf Edwards remains regular, and MacColl alters his singing to accommodate changing stress patterns of the lyrics’ syllables. This is as opposed to the changing of pace of the beat that occurs in other songs. Occasionally, he adopts this approach even in unaccompanied songs, such as the grand ballad ‘Captain Wedderburn’s Courtship’.

In the accompanied ‘The Bold Poachers’, there is no doubt about the ballad’s regular 4/4 background, but MacColl’s singing both speeds up and slows down the pulse in the course of singing as the narrative suggests, creating a rhythm that Edwards tends to follow. As the song progresses, it generally slows too, matching the listener’s growing realisation of the severity of the narrative (the first three verses are around 15 seconds long, the following three 16-17 seconds and two of the final four reach 18 seconds).

His late recording of ‘Sheath and Knife’ is the locus classicus of his focus on melody, as MacColl takes all the time in the world and yet will rush words when appropriate – compare only the first and third lines of the first verse. At the end of each of these lines, MacColl drops away in pitch and air pressure, almost preparing for the introspective line that makes the refrain, which MacColl sings almost sotto voce. In this third approach, MacColl seems more extreme than any of the recorded source singers (Harry Cox, Phil Tanner, Walter Pardon, etc.), someone for whom songs were felt to both affect and reflect real life, embodying aspects of the singer’s own history and lived experience, hence his ‘policy’.

Although MacColl was in utter control of his pacing, his pitching, tone and performances appeared delivered on the spot, contributing enormously to how he could hold an audience. His singing still has a great deal to teach those who live the tradition.