Tuesday, February 14, 2023

How Wesli is rewriting tradition by combining ancient and modern sounds

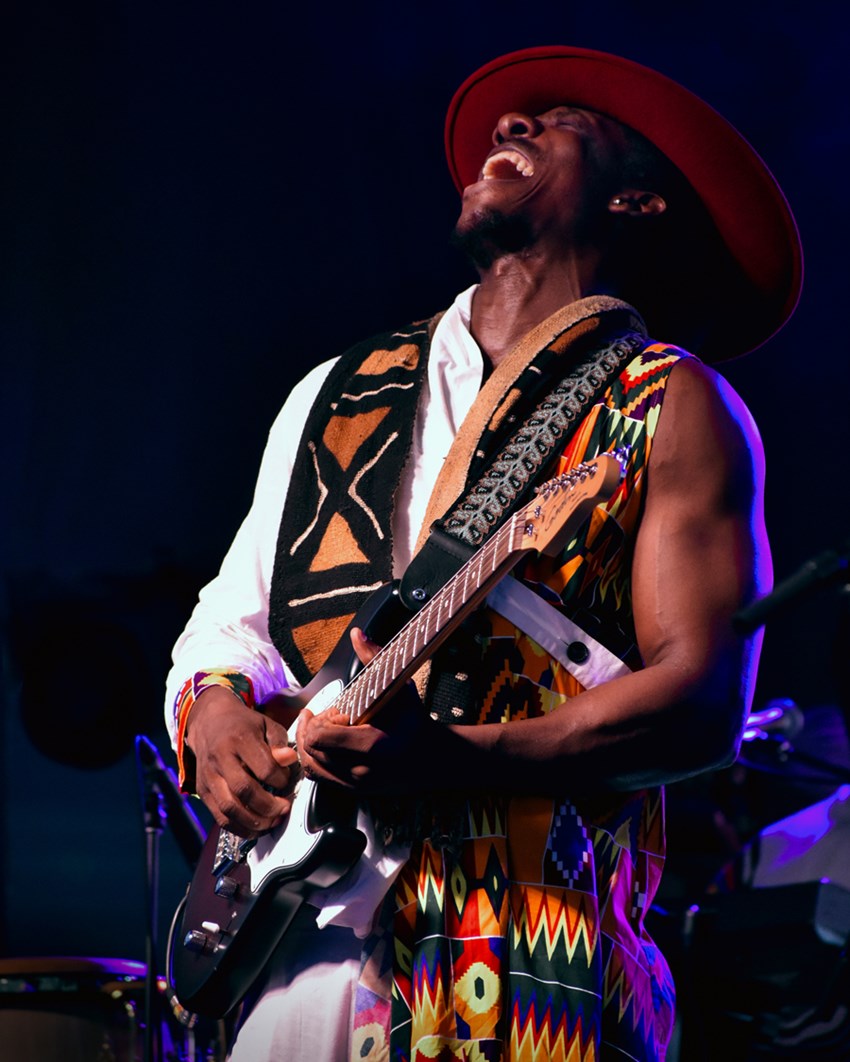

Philip Sweeney traces Wesli’s journey from the slums of Haiti through Cuba, Canada and Paris in search of an alternative Haitian music that is neither pop nor traditional

Cité Soleil, the squalid, tin-roofed bidonville by the airport of Haiti’s capital Port au Prince, is in many senses a long way from the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris where the lavish new Canadian Embassy is located. Around the corner from the Élysée Palace, the embassy is surrounded by luxury boutiques, estate agents selling multimillion-euro flats and antique dealers dazzling with gold rococo mantel clocks. Wesley Louissaint – Wesli by stage name – sits at a white conference table in the embassy’s sleek new cultural centre, in whose immaculate 100-seater theatre he is due to play in the evening; Wesli and Canada go back a long way. “I always kind of knew as a child I had a talent for music,” he says, “but it was the Canadians who gave me the chance to be who I am today.”

In return Wesli, as a textbook member of Montreal’s celebrated multi-ethnic population, is providing the Canadian diplomatic service with a perfect showpiece for the arts projects with which it enhances its cultural soft power. “We put on 20 or 30 concerts a year, all free. The Haitian artists are the ones who get the audience dancing,” Caitlin Workman, director of the Paris cultural centre, tells me. “We’re keen on inclusivity, disabilities, LGBTQ+. We connect with artists visiting on tour or launching records.” Step forward to Tradisyon, Wesli’s newly released seventh album, a polished collection of traditional songs treated to updated arrangements of unusual taste and subtlety, proposing, he says, “a formula for combining ancient and modern sounds.”

Wesli was born in Cité Soleil to musical parents from the north-eastern Haitian town of Port-de-Paix who had joined the influx from the countryside in the 1980s. “My mother sang in a church choir, my father played twoubadou-style banjo on the beach – he played with some important musicians,” the great 1960s compas star Coupé Cloué and seminal country twoubadou Ti-Coca among them. “Cité Soleil was poor then, but not like today” – subsequently the district became notorious for robbery, kidnappings and shoot-outs between gangs and police. “It started as a place to welcome people into the capital, but soon it became a place everyone wanted to get out of.”

Wesli’s first escape from Cité Soleil was to Cuba, no less, a country with strong musical links to Haiti, via the waves of Haitian coffee and sugarcane labourers who left to earn a pittance in the neighbouring island. “I left aged 11, my father wanted us to escape the violence after 1991.” This was the year of the coup that deposed Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the democratically-elected politician-priest who followed many years of dictatorship. “My father already knew Cuba, he’d been to Maisí and brought back a hybrid banjo-tres. We set off in a small boat…” But this was the period of US president George Bush’s policy of intercepting refugees before they could reach their shores. “We were stopped at sea by the US Coastguards. They took us to a refugee camp inside Guantanamo Bay. I stayed there for a year and was then taken back to Haiti with the US Marines who returned Aristide to power.”

Back at school, Wesli immersed himself in music. “I started by making my own instruments, out of an oil can and nylon line, and I learned by watching my father’s hands on his banjo.” Then fate, in the shape of the Canadians, intervened. “The Canadian Embassy in Haiti had a competition for young musicians. I won, and the prize was a nine-month scholarship in Montréal.”

Wesli thus became one of the 138,000 Haitians who constitute the largest immigrant group of Canada’s most diverse city, a community whose vocabulary has spread out of the Haitian district of Rivière-des-Prairies, larding Eastern Canada’s youth slang with items like ket for ‘great’ and pouchonne for ‘sexy girl.’ Ambitious, energetic and engaging, he rapidly made friends and local artists and DJs were among the numerous collaborators of his rapidly-blossoming gig and recording career. In particular, reggae and African sounds drew him in and he soon became part of the entourage of the annual Nuits d’Afrique festival and its associated local nightclub the Balattou. It was here, around 2010, that Jacob Edgar, founder of the world music record label Cumbancha, first discovered Wesli’s “rare natural talent and unbridled creativity,” at the same time as Wesli continued to gravitate towards the world music scene rather than the Haitian market.

A decade later, by now a resident of the hipster district of Plateau and proprietor of a small recording studio, Wesli’s aesthetic aims had moved firmly towards Haitian roots rediscovery rather than the formulaic compas (kompa or konpa in Creole) dance music of popular Port-au-Prince bands like T-Vice, or its successor genre, facile consumer Haiti pop. Thus began a series of trips back home to investigate the song repertoires of the lakous – Haitian village community associations – which formed a major source of his work.

Wesli has retained links in all camps, however. He opens his Paris concert with a minute’s silence in memory of a figure most of the audience will surely never have heard of, one Michael Benjamin, aka Mikaben. Former star singer of the famous Haitian group Carimi, Mikaben died of a heart attack mid-performance at Paris’ giant Accor Arena a fortnight earlier, having made history with the first Haitian pop concert to attract over 10,000 punters. A childhood friend, Mikaben is a virtual Dorian Gray portrait of what Wesli hasn’t become. The son of the famous ‘Christmas singer’ Lionel Benjamin, a sort of twinkly old Creole Bing Crosby who is still wheeled out by Haitian TV every December, Mikaben’s fame is built on ultra-lightweight compas love video hits like ‘Hello Baby’ and ‘Baby I Miss You’ featuring tuxedo-clad canoodling with skimpily-dressed models, far removed from the aesthetic of Wesli’s new focus on cultural authenticity and musicological exploration.

Though Wesli has ventured into Mikaben territory, as the video of the pair’s joint single ‘J’ai Grandi Dans un Ghetto’ attests. All singalong choruses and adorable dancing tots, it’s a well-intentioned production – “I made the record to show children from the slums that they could have a bright future too” – but artistically it verges on Mikaben territory nonetheless. Has he ever thought of going the whole pop anthem hog with a full complement of synthesizers, swimwear models and sports cars? Unsurprisingly, the answer is negative. “It’s only fun making music that you feel is significant,” says Wesli. “I consider what I do Haitian alternative music, not Haitian pop or compas. But I’m not just a traditionalist. You’ll see when volume two of Tradisyon comes out. I’ve already recorded it and it’s much more modern. I combine traditional songs with electronica and disco, like Mory Kanté did years ago with ‘Yeke Yeke’.”

For the present record though, two distinct styles stand out. Firstly, the Cuban-influenced folk of troubadou, for which Wesli’s great empathy, skill and sensitivity were presumably imbued by his father and by early mentor, the guitar virtuoso, Toto Laraque. “I’d love to get my dad to record again,” he comments, “he gave up music decades ago. My mother always said I should make money at music as my poor father never did.” Wesli certainly deserves to. Tracks like ‘Kay Koulé Trouba’ and ‘Makonay’ stand as equals to the lovely 1990s work of Miami producer Fred Paul’s landmark Haitiando series, thanks to the Tradisyon cast of double bass, accordion, shaker percussion, subtly-innovative sweeps of violin and cello, Wesli’s jaunty banjo and the atmospheric embellishments from one of his instruments, locally-made by the prestigious Québécois guitar manufacturer Godin. “I recorded the roots tracks in Haiti,” Wesli comments, “because of the special sound you get there with old school mixers. Haitian music from Montreal or Miami is much brighter but less authentic sounding.”

The other great triumph of the album consists of the Afro-derived percussion and chant tracks, connected either to rara carnival music, or to vodou ritual, including songs in homage to the pioneering 1990s vodou performance groups of Racine Mapou de Azor and Wawa & Rasin Ganga. What is his relationship to vodou? “I respect and love the vodou religion as part of Haitian culture,” he explains, “but I’ve never posed as a houngan, a priest or shaman. I’m nearer to a samba, which is a member of the congregation who plays and sings the ceremonial songs.”

Is Wesli tempted by politics, which is often linked to music in Haiti? (Ex-president and compas star Michel ‘Sweet Micky’ Martelly is still combining both activities to controversial effect between Port au Prince and Miami…) Wesli is circumspect. “No, because politics in Haiti is manipulated by outsiders. Haitian politicians have no real power. I just think it’s sad for Haiti, the first black republic, to be in such a mess.” Since we’re in view of the Eiffel Tower, at least from the Paris embassy’s rooftop garden, what does he make of the recent American media claims that the tower was built with money siphoned from the Bank of Haiti by the Parisian CIC bank? “Well, it’s true that Haiti’s independence was crippled by reparations to France for damage during the slave revolt… but you have to see things positively now, I believe in reconciliation and tolerance.”

Read the review: Tradisyon

This interview originally appeared in the January 2023 issue of Songlines magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today