Tuesday, July 14, 2020

Music in the time of Coronavirus

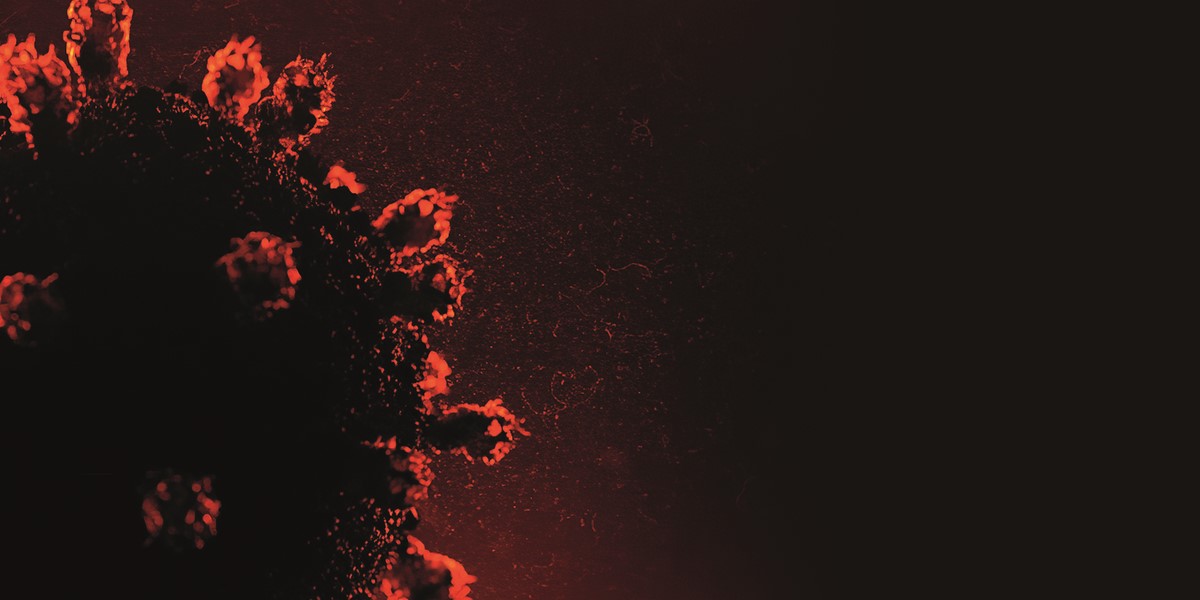

COVID-19’s impact has been global and unprecedented. Russ Slater speaks to various musicians and people who work within the music community about how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting their approach to making and promoting music

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting the Songlines website, your guide to an extraordinary world of music and culture. Sign up for a free account now to enjoy:

- Free access to 2 subscriber-only articles and album reviews every month

- Unlimited access to our news and awards pages

- Our regular email newsletters