Thursday, August 13, 2020

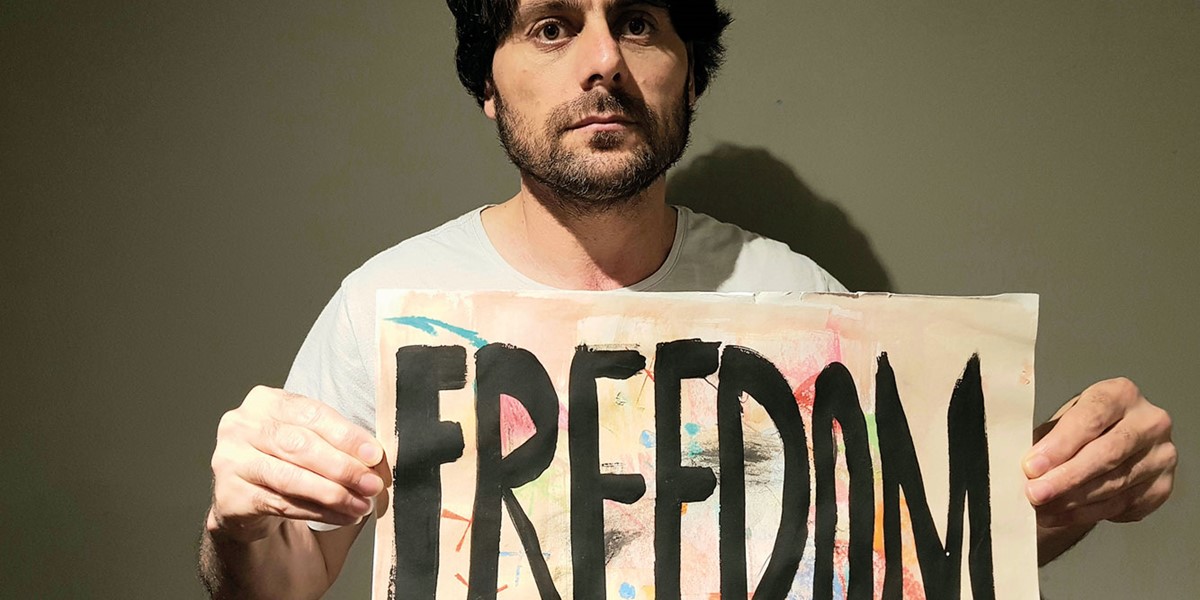

Musicians in Detention: “These people are hiding in plain sight, and rotting away”

Australia’s hardline treatment of refugees is under fire as high-profile artists join the campaign in support of two detained Kurdish musicians: Farhad Bandesh and Mostafa ‘Moz’ Azimitabar. Jane Cornwell reports

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting the Songlines website, your guide to an extraordinary world of music and culture. Sign up for a free account now to enjoy:

- Free access to 2 subscriber-only articles and album reviews every month

- Unlimited access to our news and awards pages

- Our regular email newsletters