Wednesday, October 19, 2022

My Instrument: Noor Bakhsh and his benju

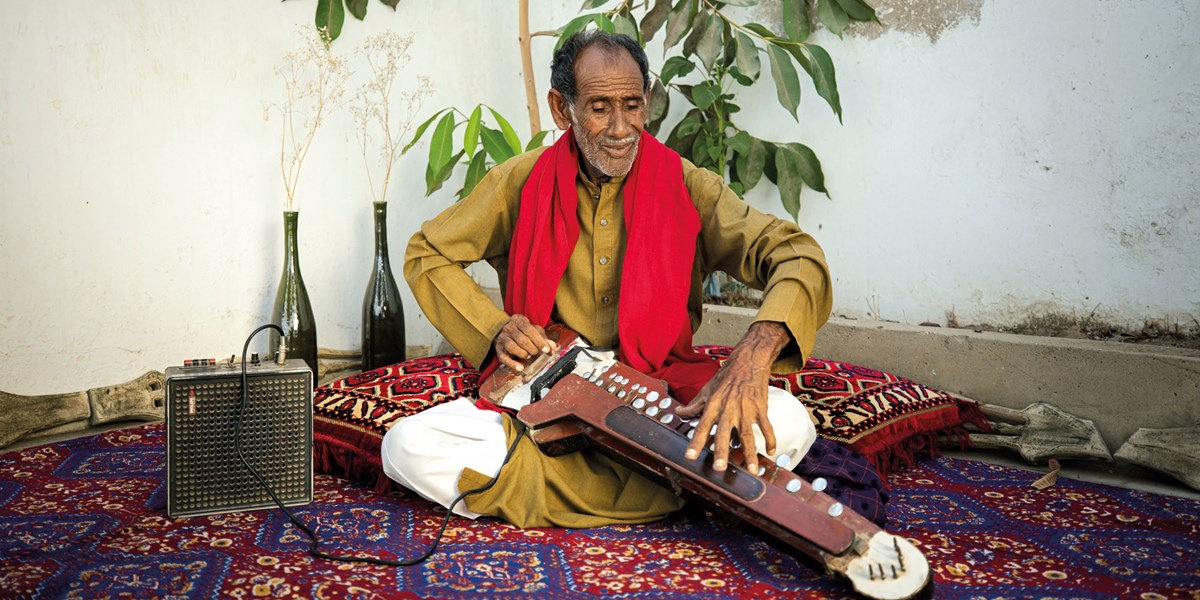

Chris Menist speaks to the Pakistani master of the keyboard-fitted zither, which holds a central role in the music of Balochistan

On first appearance the Balochi benju looks like a slide guitar with typewriter keys. It’s unique to the Balochistan region of Pakistan, which borders with Iran and Afghanistan, and yet it has seemingly unconnected cousins in the taishōgoto of Japan, the akkordolia of Germany or Sweden’s nyckelharpa. It’s closest comparison is the bulbul tarang or shahi baaja in neighbouring India.

Thanks to a series of recent Instagram posts that went viral, one of the best known exponent of the benju is Noor Bakhsh, a musician steeped in the folklore and culture of the region, but relatively unknown globally until the wonders of social media. “I was a small kid when I got interested in the benju, in musicality and in musical forms. My teachers were Ustad Khuda Bakhsh and Ustad Rehmat,” he says. “I was madly in love with the sound of this instrument. I can play all kinds of tunes: Arabic, English, Saraiki, Urdu, and Balochi is of course our own thing.”

Like many master musicians, Bakhsh appears completely at ease with the benju, the technical flourishes and melodies flowing out of him in an endless stream of sound. Through repetition and speed his performances can lean towards the ecstasy of Sufism and qawwali. “My qaum (community) is called Zangeshahi,” he explains. “We have many musicians in our community, even the smallest kid wants to play music and instruments. Everyone is a natural musician. This is our tradition, we are meeraasis [inheritors of a musical family]. I don’t know how old I was when I started learning, but I can tell you that one kilo of sugar cost two rupees!”

The instrument itself is largely constructed of wood with the addition of metal strings, and the aforementioned keys. The amount of main strings and complementary drone strings depends on the player, as while it is part of an old musical tradition there appears to be some flexibility. “Normally the benju has six strings, but mine is electric. In the middle I have only one string, so five strings in total. The middle string is called zubaan (tongue), this is the one that speaks. Then there are these two other zubaans as well. They are all tuned to Sa [the root]. And the other two strings, called the bam, which are the drones, are tuned like this, to Pa [the fifth].”

The versatility of the instrument is fully on display in Bakhsh’s performance for the debut edition of Boiler Room Pakistan, filmed live in Karachi, and will be further heard on his forthcoming EP release, Jingul, on the Honiunhoni label, recently set up by musician and anthropologist Daniyal Ahmed. It was also Ahmed who travelled to Bakhsh’s home village to film those now popular Instagram videos, as well as record the whole album outside, in a similar manner to his live performances.

Due to Balochistan’s geography, myriad influences can be heard in Bakhsh’s playing, be it melodies from the Arab Peninsula, Iran, various ragas from Pakistan and India, and echoes of past masters such as Bilawal Belgium or the double flute player Misri Jamali Khan. For Bakhsh, though, his music connects with something more elemental that perhaps lends it its timeless appeal. “Birds make different kinds of sounds, but it’s about how they are memorised in the imagination,” he concludes. “You see it’s about how one can find inspiration from them to create original tunes. When I hear the birds sing, I try to tune my benju to their voices.”

Noor Bakhsh's Jingul is available via the Honiunhoni label

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Songlines magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today