Wednesday, September 14, 2022

Rhythm Nation: Jamaica's 60 Years of Independence

By David Katz

With Jamaica marking the 60th anniversary of its independence this year, David Katz traces the sounds that built a nation, marvelling at the island country’s remarkable aptitude for musical innovation

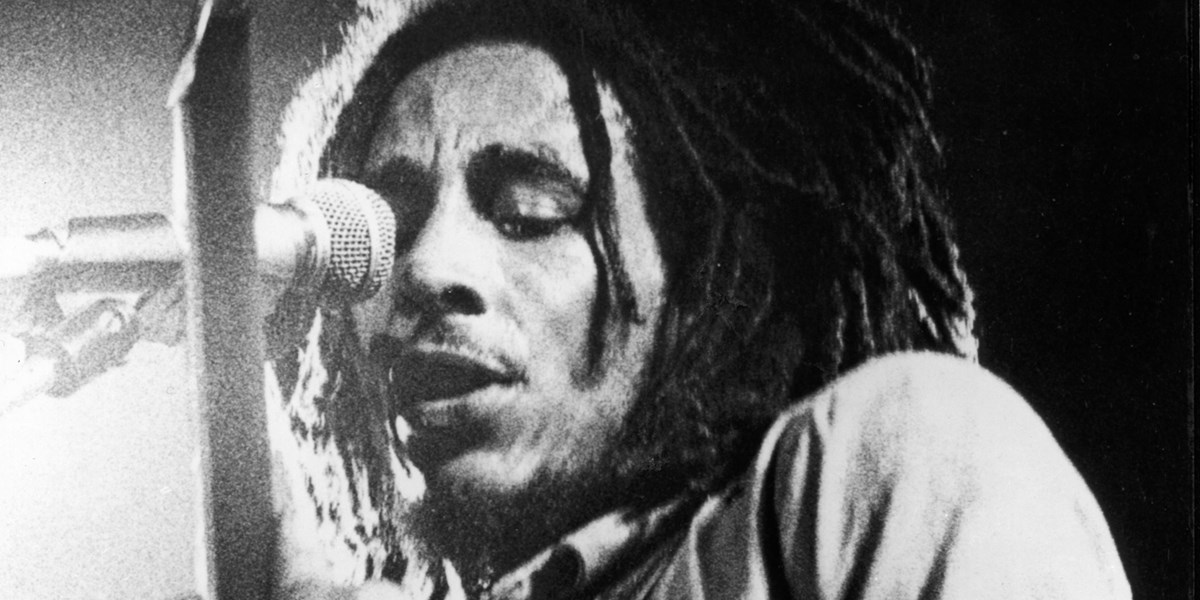

Bob Marley

By the time that Jamaica achieved its independence from Britain on August 6 1962, its fledgling music industry was already impacting audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. The dynamic hybrid of ska was indelibly linked to the independence movement, its unique emphasis on the afterbeat emerging as part of the quest for identity as the island strove to shake off the colonial yoke and claim its own place in the world.

As trade union leaders Alexander Bustamante and Norman Manley fought for better working conditions for the Jamaican public and the right to self-determination, The Skatalites were breathing life into ska, reportedly at the request of Studio One Records founder Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd after he witnessed its members playing wild jazz jams at percussionist Count Ossie’s Rastafari encampment in the east Kingston hills. “I think Mr Dodd asked for a Jamaican music,” Skatalites saxophonist Tommy McCook once said in a radio interview. “He said to experiment and came with the ska thing, which was really the swing and the guitar playing the upbeat.”

The Skatalites (courtesy of Heartbeat Records)

The Jamaican recording industry began in the early 1950s, when a handful of entrepreneurs released 78s featuring the local folk form known as mento. The Jewish-Jamaican businessman Stanley Motta was the first to open a tiny makeshift studio in downtown Kingston. By the late 1950s, emulating imported records from the US, rivals such as Ken Khouri of Federal Records, future Island Records founder Chris Blackwell and future prime minister Edward Seaga of the right-wing Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) were all recording artists that played the jump blues popular in New Orleans. Laurel Aitken was one of the most prominent of these artists until Theophilus Beckford’s ‘Easy Snapping’ in 1959 pointed to the afterbeat emphasis, which would subsequently demarcate ska.

Ska struck a chord with the mods in Britain, as well as with Jamaican expatriates, and as post-independence Jamaica sought to foster a national identity, a ska delegation was dispatched to perform at the World’s Fair in 1964 to increase the reach of the distinctly Jamaican music. Jimmy Cliff and Prince Buster were among the featured performers, although the uptown band Byron Lee and the Dragonaires were selected by Seaga to back these artists rather than The Skatalites as he wanted to break the perception of ska as the music of a suffering underclass. “Eddie Seaga was the politician in whose constituency ska was,” said Lee, when I visited his recording studio in 1998. “In 1962 he sent us down there to study the music, as he wanted to be the minister of culture who said, ‘I have given you a music from the ghettos of Kingston to celebrate our sovereignty of independence.’ We knew nothing about ska until Seaga sent us down there. It was being played down in the western sound systems, but it was kept down in the ghetto and wasn’t recognised by the people mid-town and uptown who could afford to buy it and support it. It was not played on the radio stations, because they wouldn’t accept the quality – the guitars were out of tune, the records [would] hop, skip and jump. We took [the music] along… with the people who produced it, exposing them to the uptown people who looked down, saying, ‘That is music for the poor people, we don’t want to be associated with it.’ But we crossed the barrier and brought it up, because Byron Lee was accepted by the middle, up-class.”

Laurel Aitken (courtesy of Top Beat)

“I took Byron because he was somebody that I knew,” said Seaga, who held his constituency meetings at one of Kingston’s most popular dance halls. “I said, ‘You need to come hear this beat.’ He came down, heard it and tried it uptown, but it didn’t work because uptown people are different from downtown people. It was when ska left Jamaica and went to England as blue beat that it became popular over there. After becoming popular in London, uptown people started to accept it.”

Unlike the mento producers, who were entrepreneurs with prominent downtown retail businesses, the pioneering ska producers were all sound system owners who began producing music as a means of keeping audiences loyal through exclusive material initially retained on acetates, or dub plates, which would later gain a general release. The most important figures included former policeman Duke Reid, his younger challenger Clement Dodd, and King Edwards, a staunch supporter of the left-leaning People’s National Party (PNP) who ran a liquor store and record shop in western Kingston together with his brother. Dodd’s former henchman, Prince Buster, soon emerged as formidable competition too, but Dodd was the frontrunner in ska, his Studio One recording facility and group of labels responsible for leading hits by Bob Marley & the Wailers, Toots & the Maytals and Ken Boothe, among many others. “My memories of the days of Duke and myself, the rivalry was more like a musical challenge,” said Dodd. “With importation, I had the stronger set of records, and also when we started recording locally.”

Duke Reid (courtesy of Heartbeat Records)

Nevertheless, Duke Reid got his own back in the mid-1960s, when ska’s furious pace and big-band jazz arrangements gave way to the cooler rocksteady style. The Duke’s newly-constructed Treasure Isle studio became the home of rocksteady, with soul-influenced hits by the Paragons and Alton Ellis ruling the roost, but he lost dominance by 1968, when the new reggae style took the island by storm through a fast-paced dance style based on an organ shuffle as a new production vanguard emerged including Clancy Eccles, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Harry J, their oddball organ instrumentals making inroads with skinhead audiences in Britain, as well as the Caribbean diaspora.

But Jamaican popular music never sits still for long; by 1970, the predominant style had changed again, this time to the slower, heavier style of roots reggae, with its focus on social issues and Black liberation, its hitmakers often speaking from a Rastafari perspective. “When I went out there [on the scene] and did my thing, the music wasn’t in that flavour or arrangement,” said Burning Spear, who was one of the first to make an impact in roots reggae. “So I think I brought a newness at that time.”

During this time, Norman Manley’s son Michael, a charismatic trade unionist, became leader of the PNP and was elected prime minister in 1972 after adopting Delroy Wilson’s social protest anthem ‘Better Must Come’ as his campaign song. Two years later he introduced an agenda of democratic socialism, launching a large-scale literacy drive, improving public access to employment, housing and rural development schemes, but strengthening ties with Fidel Castro set off alarm bells in Washington. Bob Marley & the Wailers signed to Island as Manley began his ascendancy, singing of the need to set Kingston ablaze and to firebomb churches ‘now that we know the preacher is lying,’ and another of the label’s top reggae acts, Third World, included among their members guitarist Cat Coore, son of Manley’s deputy David Coore. After a bitterly fought campaign that saw neighbouring communities attacking each other, resulting in hundreds of deaths, Michael Manley was re-elected in 1976, the internecine battles linked to the broader Cold War politics at play in the region explored in songs such as Max Romeo’s ‘War ina Babylon’, the Gladiators’ ‘Mix Up’ and Prince Far I’s ‘Heavy Manners’.

Clement Dodd (courtesy of Heartbeat Records)

But roots reggae wasn’t just about party politics. Dennis Brown also enjoyed spectacular success with the dejected ‘Money in My Pocket’ and Gregory Isaacs with the suggestive ‘Night Nurse’, showing that reggae love songs could be just as popular as hard-hitting songs of social commentary. Dub music had also made major inroads overseas in the 1970s, with albums by King Tubby and the Mighty Two proving popular with punks, hippies and stoners thanks to the form’s use of remix trickery and mind-bending sound effects.

In the aftermath of Bob Marley’s death in 1981 and Jamaica’s shift to a free-market agenda under Seaga, the music reinvented itself once again as the more urban dancehall style came to the fore. With an absence of interest from foreign labels, the music’s focus became more insular, preoccupied with local concerns and with lyrics often addressing sensual pleasures, rather than current affairs or social issues. As Sugar Minott once explained, “it’s not every time you want to tell somebody, ‘them bombing up Belfast.’ People just want to hear songs that make them feel good.”

Then, in 1985, once label owner King Jammy unleashed Wayne Smith’s ‘Under Mi Sleng Teng’, which was based on a Casio keyboard pre-set, Jamaican popular music changed overnight, with producers opting for sequenced, synthesizer-driven minimalism, with deejays such as Shabba Ranks and Lady Saw giving upfront depictions of graphic sex and artists like Ninjaman glorifying gun violence in their lyrics.

By the early 90s, the music made another shift, following the popularity of Garnett Silk, who sang of pertinent issues from a Rastafari perspective; the resultant ‘Rasta Renaissance’ saw Luciano become a major overseas star as Jamaican music began making greater use of live instruments once more, his ability to equally ride rough dancehall rhythms and finely crafted complex works making him a favourite of roots fans and dancehall devotees. “I realised that my singing had to have a meaning,” Luciano explains. “My voice kind of leant itself to hardcore roots because it would seem that the baritone voice is a more beckoning voice to gather the people, other than to giving a little romance. So, I could make the dancehall become more like a lover’s rock, and I realised that one could want to say so many things, but without the right melody, people would not be willing to listen.”

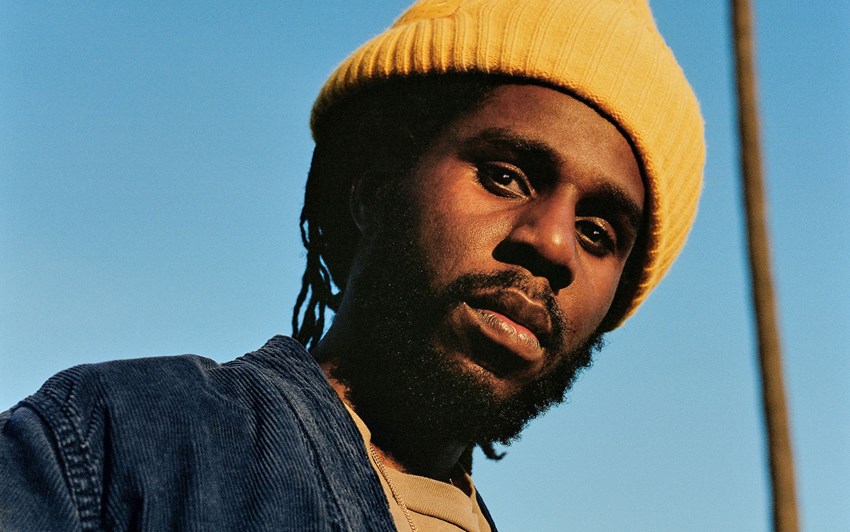

Chronixx (photo: Harry Eelman)

During the late 90s and early 00s, Jamaican music was split between hardcore dancehall’s excessive figures, with artists such as Buju Banton and Beenie Man embroiled in overseas boycotts for homophobic lyrics, even Sean Paul became a ubiquitous collaborator, following the commercial success of ‘Gimme the Light’. In more recent years, the ‘Reggae Revival’ movement has aimed to return Jamaican music to the values that helped roots reggae reach its apex, with Chronixx making the greatest impact through a readily identifiable vocal style and perceptive song-writing abilities; jazzy songstress Jah9 and the relaxed raps of Protoje have also commanded strong followings.

What’s next for Jamaican popular music? Electronic dance music and Afrobeats are areas of growing interest for the island’s music producers and the Grammy win by lewd dancehall artist Spice points to dancehall’s continual importance, yet the constant shifts in style and form make the future of reggae difficult to predict.

Happy 60th, Jamaica. May your coming years be peaceful, fruitful and stable, and may your music continue to impress.

Read the album review: Rise Jamaica! Independence Jamaica Special

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2022 issue of Songlines magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today