Thursday, June 13, 2024

Salif Keita: “The youth are into machines… We are about to lose our traditional instruments”

After announcing his retirement in 2018, Malian singer and musician Salif Keita has slowly returned to the spotlight following a series of shows last year. Now, he’s making the comeback official with an extraordinary new album

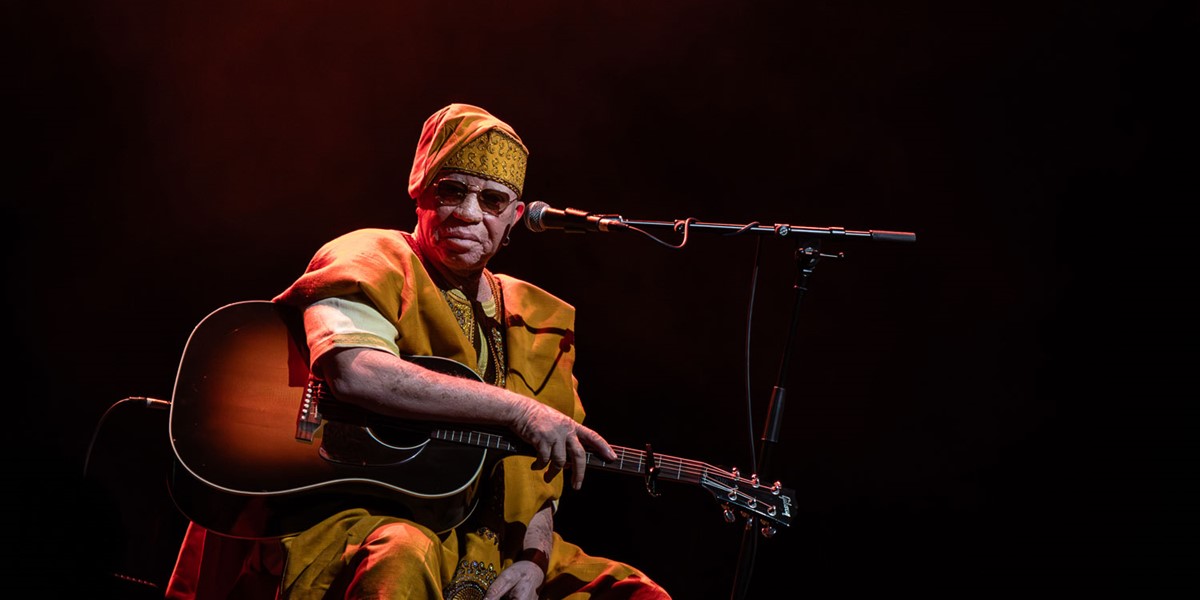

Salif Keita at the Barbican for Songlines’ 25th anniversary (photo: Jamie Hodgskin)

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting the Songlines website, your guide to an extraordinary world of music and culture. Sign up for a free account now to enjoy:

- Free access to 2 subscriber-only articles and album reviews every month

- Unlimited access to our news and awards pages

- Our regular email newsletters