Thursday, December 12, 2024

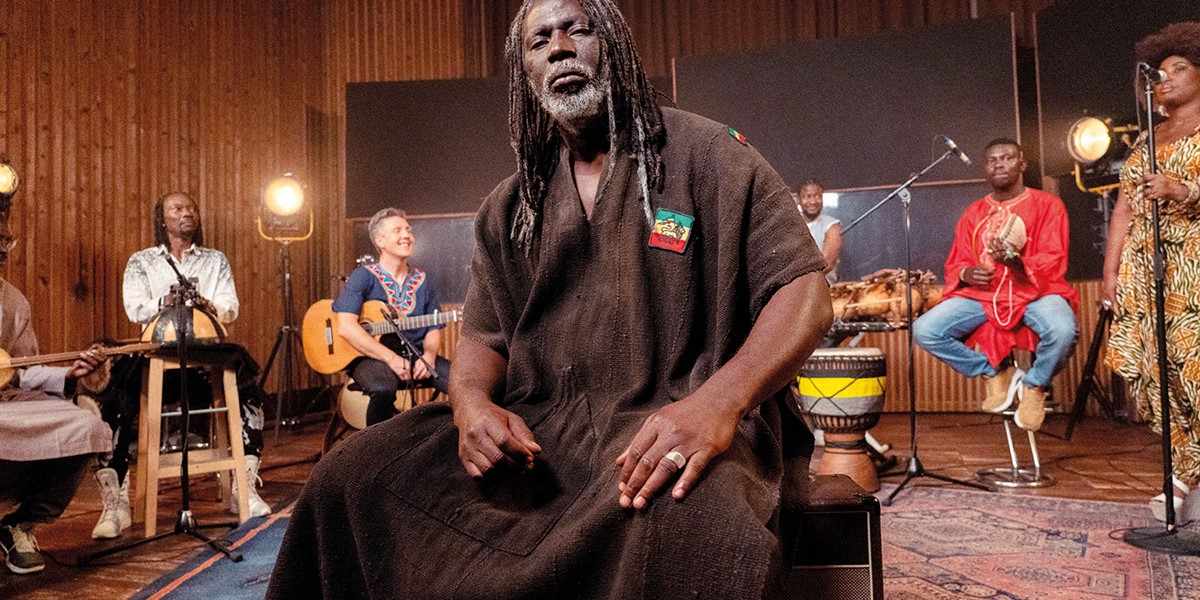

Tiken Jah Fakoly: “In Africa, I can’t perform as much as I’d like. Sponsors are afraid of my image”

By Daniel Brown

During his career, Tiken Jah Fakoly has fused reggae with unwavering pan-African activism. The Ivorian reggae icon speaks to Daniel Brown about his latest release and how the fight for justice in Africa is far from over

Tiken Jah Fakoly (photo: Youri Lenquette & Frank Loriou)

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting the Songlines website, your guide to an extraordinary world of music and culture. Sign up for a free account now to enjoy:

- Free access to 2 subscriber-only articles and album reviews every month

- Unlimited access to our news and awards pages

- Our regular email newsletters