Tuesday, July 17, 2018

The Rough Guide to World Music: Jamaica

Jamaica is a serious contender for the title ‘loudest island in the world’. On any night, and especially at weekends, it shakes to the musical vibrations of thousands of sound systems

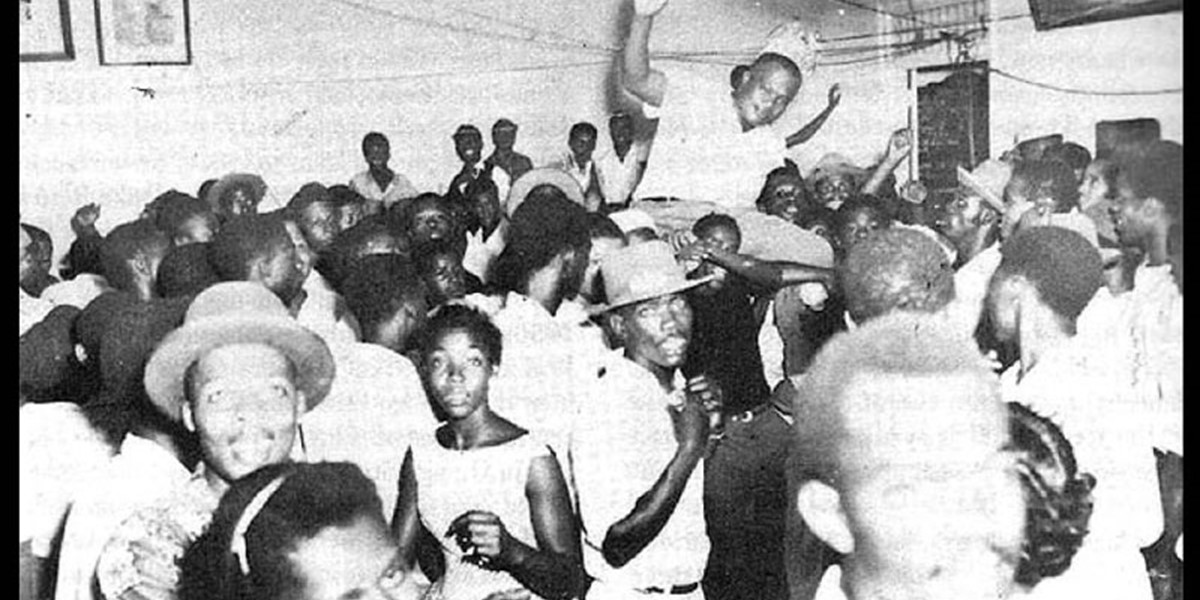

Duke Reid crowned “King of Sounds and Blues”, Success Club, Kingston, late 1950s

Note that this Rough Guide to World Music article has not been updated since it was originally published. To keep up-to-date with the best new music from around the world, subscribe to Songlines magazine.

Jamaican music has been a global force for the last thirty years – a remarkable feat, considering the island's tiny size and population – yet many of its diverse strands are hardly known. Gregory Mthembu-Salter and Peter Dalton dig up the island's musical roots – maroon, religious and carnival music, mento, ska and rock steady – to find the sources of the great Caribbean powerhouse that is reggae music.

Introduction

Jamaica is a serious contender for the title ‘loudest island in the world’. On any night, and especially at weekends, it shakes to the musical vibrations of thousands of sound systems, revival sessions, grounations, Maroon and Kumina possession ceremonies, and old-time mento dances. Tens of thousands of radios, cranked up to full volume, add to the hubbub. Inevitably, the sounds with the most wattage grab the limelight, but other musical styles have proved enduring. Some have been around on the island for four hundred years.

Tell it to the Maroons

In 1492, the history books tell us, Jamaica was discovered by Christopher Columbus. “Christopher Columbus was a dyam liar,” reply Jamaicans, “The Arawaks was here first.” And so they were. The Spanish who followed Columbus, however, saw fit to carry out the genocide of the island’s original population and by the time Oliver Cromwell’s navy wrested the island from the Spanish in 1670, they had been wiped out. In their place were small numbers of African slaves, mostly from Ghana, who had been armed by the Spaniards and instructed to defend the island from the British while they themselves escaped.

Most took to the hills instead, to remote parts with names like Me No Sen, You No Come, where their descendants, the Maroons, live in their own secluded communities to this day. They forged a percussive style of music, still played today at possession ceremonies – religious rituals in which the musicians and dancers get increasingly frenzied as they become possessed by whichever type of spirit, ancestor or god they have invited to the occasion. The music is available on a couple of well-annotated discs (see discography), which point to the roots that nourished reggae.

With colonisation came plantations, which were thrown into turmoil by the Abolition of Slavery in 1838. Despite prolonged advance warnings, few plantation owners had bothered to restructure their operations, and more slaves continued to die than be born on their estates. Faced with a diminishing workforce, planters resorted to devious devices. A number of Angolans were brought over in ensuing decades under the guise of ‘indentured servants’. These people seem to have been the main constituents of the Bongo Nation, who are responsible for the religion and music known as Kumina. The music, again available on a couple of ethnographic recordings, takes a similar form to Maroon music.

Maroons and the Bongo Nation make up a tiny proportion of Jamaica’s population. Few others were able to preserve their African cultural identities in such an undisturbed fashion. But although the repressive system severely curtailed music-making, an extremely rich folk tradition emerged on the island, and one drawn from an amazing range of creative sources. In the enormous canon of Jamaican folk music, there are traces of African, British, Irish and Spanish musical traditions, and heavy doses of Nonconformist hymns and singing styles. Each of these influences is blended with characteristic Jamaican wit, irreverence and creativity. There are songs for courting, marrying, digging, drinking, playing ring games, burying – and just for singing, too. One of the classics is “Hill and Gully Rider”, a timeless ode to transport on an island strong on hills and weak on roads.

Unfortunately, few of the available recordings of this folk music are of much value. Most seem to have been made by earnest ethnomusicologists in the 1950s, recording people plainly embarrassed to have a huge microphone put in front of them. When in Jamaica, however, you can hear examples of it, particularly in the country areas, and it has regularly emerged as an element in the stark, minimalist modern dancehall music. As DJ Admiral Bailey says, “Old time someting come back again”.

Gimme that Old-Time Religion

As well as being extremely loud, Jamaica is also extremely religious. If you get up early on a Sunday morning, and walk from town into the ghettos, or into the hills, you pass by an incredible variety of religious ceremonies, each with its own music. From the graceful plantation-era buildings of the Anglican Church come the thin, reedy voices of middle-class Jamaica, struggling with turgid Victorian hymns. From smaller churches further along emanate the more boisterous melodies of the Nonconformist churches, and, further still, the tambourine-shaking sounds of the Pentecostal denominations. But up in the hills -– and down in the ghettos – can be found the jumping sounds of Pocomania and Revival Zion.

Both these Churches date from the early 1860s, when a great religious revival swept through Jamaica. Both draw on Christian and African traditions, with more Christianity in Revival Zion, and more Africa in Pocomania. As in the Pentecostal churches, both types of service feature much Bible-reading, tambourine-rattling and foot-stamping, but unlike the Pentecostal churches, they also use persistent and hypnotic percussion, and trumping. Trumping is the process that leads to possession, and involves moving in a circle, often around a symbolic object, like a glass of rum, and breathing very deeply. Worshippers grunt as they rotate, faster and faster as the spirit possesses them. The combination of trumping and drumming is unforgettable and recordings – though available – don’t do it justice. However, the Poco sound, with its powerful, rolling side-drum patterns, has, like Jamaican folk, turned up in a dancehall mode.

Most Jamaicans are Christians. As is well known, however, a sizeable minority are not, including, most notably (at least in musical circles), the Rastafarians – of whom more below. Often ignored are Jamaica’s Hindus – people of Indian origin who, like the Angolans of the Bongo Nation, were ‘indentured’ to the plantations after Abolition. Though most intermarried, there is still a distinctive Jamaican Indian culture and associated music, though not on the scale of Trinidad, where Indians settled in far greater numbers. Again, Jamaican roots discs include intriguing examples of their baccra music – Hindustan compositions often referred to by Jamaicans as ‘coolie music’.

Rastafari for I and I

Rastafarians make up only around thirteen percent of the island’s population but their influence on Jamaican music is out of all proportion. And Bob Marley is only the tip of the iceberg.

Rastafari is non-doctrinal, in the sense that it holds that no one church is powerful enough to impose its version of religious purity, and that one person’s version of it is as valid as another’s, as long as he or she is possessed of the Spirit of Jah (God). Certain themes, however, do recur, among them the belief that Jah is a living force on earth. Jah enables otherwise disparate humanity to unite. To embody this in speech, Rastas refer to each other as ‘I’. Thus I am I, you are I, and we are I and I. Such is the Rasta emphasis on the importance of the spoken word that many other words are similarly altered: ‘Unity’ becomes ‘Inity’, ‘Brethren’ becomes ‘Idren’, and so on. Unity, or Inity, is essential if Rastas are to stand strong against the wicked forces of Babylon – the oppressive (or downpressive) system.

Marcus Garvey, a forceful campaigner for black unity, pan-Africanism and a return to Africa, is of great importance to many Rastas, who revere him as a prophet. In one of his pamphlets, published in the 1920s, he urged Africans of the New World to look to Africa for a Prince to emerge. This was taken by many to mean the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie I, who claimed descent from Solomon. Selassie’s battles in 1937 against Mussolini – or the ‘wicked forces of Rome’– were taken as fulfilling the prophecies of the Book of Revelation, and he was worshipped as the reincarnate Christ. Selassie was deposed in 1974 and died a few years later, although to Rastas ‘Selassie cyaan dead’ and is living still. Rastas believe that they are awaiting repatriation to Africa – Zion – and regard themselves, and all New World black people, as living ‘slavery days’ in bondage.

From time to time Rastas hold reasoning sessions, in which matters religious, social, political and livital (about life) are discussed collectively. Larger and more protracted reasonings are called grounations. Like their Revival Zion and pocomaniac counterparts, grounations feature Bible-reading, hymns, foot-stamping and drumming. Rasta drumming (usually called nyahbingi or burru drumming), though, is much slower, with a beat more or less the speed of a human pulse. Other differences include the reasoning itself and the copious consumption of ganja – Jamaican colly weed, or marijuana. Most Rastas adore ganja and lovingly cultivate it, cure it, smoke it, brew it (non-alcoholically), use it for medicines of all sorts, and, above all, talk about it. For this, Babylon -brutalises them no end, but to little avail. As Jah Lion sings, “When the Dread flash him locks, a colly seed drops.”

Grounations occur quite frequently in Jamaica and are generally well advertised and easy to find. There are some good recordings of them, too, though inevitably they fail to capture the atmosphere and significance. By far the best Rasta music on disc are the extraordinary ‘Grounation’ sessions, performed by Count Ossie and his Mystic Revelation of Rastafari. The late Count Ossie was a master Rasta ‘repeater’ drummer from the Kingston ghetto. In the early 1960s a number of very talented musicians came under his influence, including members of the subsequently legendary Skatalites. Listen to the sessions, which also feature the great sax and flute player Cedric Brooks, and you will find astonishing Rasta drumming and chanting, bebop and cool jazz horn lines, and apocalyptic poems.

The Party Line: Mento

Religious music has left Jamaican Sundays fairly well covered, but Saturday nights have a very different sound. Most plantation owners conceded Saturday nights to their slaves, as well as the various feast days: crop-over, the yam festival, Christmas and the New Year. Plantation owners’ diaries abound with complaints of splitting headaches in the middle of the night, and even references to what seem like the forerunners of today’s sound systems. One eighteenth-century plantation owner wrote: “I am just informed that at the dance last night the Eboes obtained a decided triumph, for they roared and thumped their drums with so much effect that the Creoles were obliged to leave off singing altogether.”

The main surviving elements from all of this are mento, which draws from several of Jamaica’s folk music styles, and the Christmas carnival sounds of jonkonnu. The latter, like all the carnivals of the Americas, is a time of display, finery and revelry. Its music is traditionally played on fife and drums, and can still be heard in that form today, though calypso and mento, and whatever reggae sounds are in vogue, regularly slip in too.

Mento was recorded in the 1950s, largely by the businessman Stanley Motta, in response to the international popularity of Trinidadian calypso, which it superficially resembles. Motta recorded performers like Count Lasher, George Moxey and Lord Composer in his small Hanover Street studio in Kingston, then pressed the results in London and shipped the 78 rpm discs back for sale in Jamaica. Recent tours by and CDs of the Jolly Boys from Portland have extended awareness of mento, which was previously almost exclusively rural Jamaican. The music contains many of the elements that have made its relative, reggae, so successful. It is witty, topical, rebellious and unafraid to ‘wind and grind’. Actually, most mentos seem to come round to the subject of sex sooner or later – usually sooner. Musically, mento contains that essential shuffling strum – the ‘kerchanga, kerchanga’ – that marked out reggae from its more metronomic predecessor, rock steady.

Mento was the popular sound of rural Jamaica until the late 1940s (big swing bands were dominant in urban areas), when radios finally became both affordable and available to many Jamaicans. The new radio owners soon discovered that US stations were a good deal more lively than the stuffy local ones and before long a whole generation was going crazy over American R&B. People started flying over to the US, scouring record shops for exclusive pressings, rushing back and playing them through homemade box speakers at parties in people’s yards. Thus were sound systems born.

Sound Systems

Sound systems – essentially mobile discos – were a crucial development in Jamaican music and were to reverberate right through the next five decades, giving rise to the Jamaican record industry – the first local discs were produced for the sound systems. As early as the 1950s, the sound-system DJs would talk over the records they played, attracting custom, and the technique slowly developed into the tradition of toasting or chatting, of which more later. The earliest sound systems played the hard-edged US jump blues of such artists as Wynonie Harris and Rosco Gordon (along with balladeers like Johnny Ace), and the best known of these sounds was ‘Tom the Great Sebastian’, with the legendary Count Machuki as MC.

Another key event was the emergence of the handful of sound-system chiefs who were to become the chief record producers in Kingston. They struggled for supremacy in the open-air dancehalls amid an atmosphere of intense, often violent competition that was to become permanently associated with the Jamaican music scene. Three men soon dominated: Vincent ‘King’ Edwards, Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd and Arthur ‘Duke’ Reid – their titles perhaps an ironic tilt at the old plantation chiefs, and certainly a nod in the direction of admired US band leaders like Duke Ellington and Count Basie. At the end of the 1950s, they were joined by another contender – Cecil ‘Prince Buster’ Campbell, with his Sound Of the People sound system.

Stanley Motta had already made the island’s first recordings with mento artists, while future prime minister Edward Seaga set up WIRL (West Indies Records Ltd), mostly to press US R&B tunes. From the mid-1950s, the studios were also being used to record local R&B, at first to make exclusive recordings for particular sound systems. Beginning with sessions in 1958–59, the first local R&B discs for public sale started to appear. Employing Ken Richards & his Comets as the session band, Edward Seaga recorded one of the classics from these early sessions – Higgs & Wilson’s “Manny Oh”. Joe Higgs went on to become one of Jamaican music’s foundation figures, recording a string of hits (both solo and with his partner Roy Wilson) and tutoring many younger performers in Trench Town – most notably both the teenage Wailers and the Wailing Souls.

Seaga was one of the few early producers who did not own a sound system; another was the man who would eventually make Bob Marley a global name, Chris Blackwell. The wealthy, Harrow-educated Blackwell launched his R&B and Island labels at the close of the 1950s, soon scoring a major local hit with Laurel Aitken’s “Boogie In My Bones”, a classic example of Jamaican jump blues. In 1962, Blackwell moved to London, where he kicked off the UK version of his Island imprint with the apposite choice of Lord Creator’s beautiful “Independent Jamaica”.

The early Island label was to meet the tastes of Jamaican émigrés in the UK with releases from almost every top producer working in Kingston, including Duke Reid, Leslie Kong, King Edwards and Clement Dodd. Before long, hipper young whites in the UK were dancing to a distinctly Jamaican afterbeat, and in 1964 Blackwell had the guitarist Ernest Ranglin arrange Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop”, the international pop-ska hit.

Ska

By the mid-1960s, Jamaica’s musicians, notably the innovatory Skatalites, had established something distinctly Jamaican. Using fast R&B as their music’s basis, they cut out half the shuffle, leaving an abrupt series of off-beats. They called it ska, and it quickly took off in the dancehalls of Jamaica and Britain, where Jamaicans had begun to settle in significant numbers (see p.457). Ska bands employed much the same line-up as R&B groups, with a piano, electric guitar, stand-up bass, drums and a couple or more brass instruments. Most of the musicians came from a jazz background – swing bands were popular in wartime Jamaica – and they were world-class soloists and improvisers.

From this point on, the availability of Jamaican music improves dramatically: there were masses of ska records. The Skatalites were the masters, especially when their phenomenal trombonist Don Drummond was still alive. They were also incredibly prolific – their entire output, amounting to hundreds of records, was recorded in just fourteen months, which was the entire lifespan of the original band. Nonetheless, radio stations gave more time to the blander sounds of bands like Byron Lee and the Dragonnaires, who were patronised by Edward Seaga’s studio.

Ska is primarily instrumental, perfect for dancing, but its rhythms can be difficult to sing over. Some artists did so successfully, especially the Wailers, the Maytals, Justin Hinds & the Dominoes, Stranger Cole and future movie star and crossover act Jimmy Cliff. But the sound-system operators still needed something extra to spice up their dances. Many brought in DJs to do just that, developing the old act of talking over records into an art of its own. The greatest of the early DJs were Count Matchuki, King Stitt and Sir Lord Comic. Sadly, they were rarely recorded in this period, though Sir Lord Comic made an impact with “Ska-ing West” and “The Great Wuga Wuga”.

Jamaica became independent in 1962 and for a period the whole of society seemed infected by euphoria. You can hear it in ska’s joyous tempos, even if the horn solos often expressed a contrasting melancholy. People were flocking into Kingston every day, seeking work, money, and a better life. Some found it, but thousands never did, and settled in fast-growing shantytowns like Dungle, and badly built housing schemes, like Trench Town, Riverton City and, later on, Tivoli Gardens. From this community of the underemployed and the abused, those whom Jamaicans call ‘sufferers’, came the infamous rudeboys.

Rudeboys were young men who gave voice to their disaffection, establishing a reputation for ruthlessly defending their corner and hustling their way to their next meal or dance entrance fee. The island’s two main political parties, the Jamaican Labour Party (JLP) and People’s National Party (PNP), soon recognised their vote-garnering value. Both parties began distributing weapons, patronage and, if in government, inviolable protection to their ‘dons’, in return for bringing in the votes at election time. It was a recipe for the violence that has plagued every election to date, particularly those of 1976 and 1980.

Rock Steady

Although the last years of ska reflected the mood of the rudeboys, it was rock steady, ska’s successor, that became their sound. Over the rock-steady beat, rudeboys sang of their problems, their fears, and their ‘rude’ attitude. Typical was the song “Dreader than Dread,” by Honeyboy Martin and the Voices: if you were foolish enough not to believe them, “you’ll wind up in the cemetery, because you’ll be dead”.

The youthful Wailers had already enjoyed their first Jamaican hit with warnings to the rudies, “Simmer Down” and “Rude Boy”, and their main rivals, the Clarendonians, told of how “Rudeboy Gone To Jail”. But the most enduring rudeboy disc was the one that first brought word about the rudie phenomenon to the wider world: Desmond Dekker’s “007”, which charted in both the UK and the US. Musically, ska’s jazzy horn lines faded from prominence, while the bass, by now an electric one, grew more important and the rhythm guitar played a steady off-beat – a style that was to develop into reggae.

The slower pace of rock steady provided the perfect opportunity to express tender emotions, too. Vast numbers of love songs poured out of the studios, often with sensuous American soul tunes for their inspiration, and close harmony execution influenced by US groups like the Impressions, the Temptations and the Tams. Duke Reid’s Treasure Isle studio led the field for rock steady, with Sir Coxsone’s Studio One a close second.

The leading session bands of the period were Tommy McCook’s Supersonics and Lynn Tait’s Jets, with the Roland Alphonso-led Soul Vendors holding their own at Studio One. Besides Alphonso, the Soul Vendors also inherited another former Skatalite – the keyboard player Jackie Mittoo, arguably the most influential musician in Jamaican music’s entire history. Augustus Pablo’s early self productions, many of the Channel One and Joe Gibbs hits of the mid–late 1970s and much of the dancehall explosion of the 1980s were based on the music created by Mittoo in the rock steady, or early reggae years, and a decade after his death from cancer, the rhythms he helped build are still regularly refashioned or sampled.

Rock steady produced a string of wonderful vocal-harmony groups: the Paragons, the Techniques (at first with the great Slim Smith as lead singer, and then Pat Kelly), the Gaylads, the Heptones (featuring Leroy Sibbles, who also played many of the classic Studio One bass lines), the Melodians, the Silvertones, and the greatest harmonisers of them all, Carlton & his Shoes. The Leonard Dillon-led Ethiopians were less typical in that they showed little soul influence in their harmonising, which was rooted in a more traditional Jamaican country style; nevertheless, they had several major hits during this period, particularly with songs about trains, such as the great “Train To Skaville” (despite the title, a rock-steady tune) and “Engine 54”.

Then there was the man who gave rock steady its name with one of his many Treasure Isle hits – the incomparable Alton Ellis. Alton had started his career as half of the popular Alton & Eddie duo, performing doo-wop ballads, and then led the Flames, a trio who scored with several warnings to the rudeboys. By the close of the decade he had gone solo and was concentrating on affairs of the heart. He was rivalled only by a handful of singers – tars such as Delroy Wilson, Slim Smith (who had sung with both the Techniques and the Uniques), John Holt (formerly of the Paragons) and Ken Boothe (originally Stranger Cole’s singing partner). And proving as important a songwriter as soulful singer was Bob Andy, another major talent who has yet to receive the recognition he deserves.

Tougher than Tough: Reggae Takes Over

As the 1970s beckoned, Jamaican music changed once more when a new, lolloping rhythm called reggae hit Kingston. Producers and musicians had searched around for a new beat and hit upon the idea of incorporating the old-time mento shuffle with rock steady, thus bringing Jamaican pop that much closer to its roots. The other, perhaps more important factor in this new development involved the continuing influence of Afro-American music, and the increasing popularity of the hard-edged funk of James Brown.

This purely musical shift would have meant little, however, had it not been for other, more profound shifts that were taking place in society. Politically, there was a growing mistrust on the part of the ‘sufferers’ of the ability of the system to provide for them – and the size of their communities was growing fast. The visit of the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie to Jamaica in 1966 had also encouraged a huge growth in Rastafari, which dismissed politics as ‘politricks’, and looked instead for the return to Africa, when the captives would be set free. Rastafarian singers and musicians were increasingly asserting their right to preach their message, and to be heard.

Despite considerable misgivings, ex-policeman Duke Reid and Coxsone Dodd, the studio chiefs, had little option but to oblige. For one thing, there was the first real competition to their and Prince Buster’s cosy triumvirate. Producers who had already made something of a mark, such as Derrick Harriott, Sonia Pottinger and Bunny Lee, built on their rock steady successes to become major players. In the same period, a genuine golden era for Jamaican music, the likes of Clancy Eccles (who had been a popular singer in the late 1950s), Winston ‘Niney’ Holness, Harry Mudie, Joe Gibbs, Winston Riley (a founder member of the Techniques), and the legendary Lee Perry (see box opposite), all emerged as producers.

The list of notable artists, already lengthy, expands hugely at this point. Those who started out at this time, and are still famous, include Burning Spear, the late Dennis Brown, Gregory Isaacs and Horace Andy; in addition, several who made their recording debuts in the ska/rock steady years were making some of their best music, including Delroy Wilson, Larry Marshall, the Maytals, the Wailers and Jamaica’s greatest love balladeer, John Holt.

Wailing and Groaning

The Wailers – Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer – started life as one of many ska groups competing for attention in the mid-1960s. It was producer Lee Perry, the ‘Phil Spector of the Caribbean’, who recognised their potential, putting them together with the unrivalled drum and bass duo of Carlton and Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett from his studio band, The Upsetters. Together, they recorded a marvellous sequence of songs, which were later collected on the albums Soul Rebels and African Herbsman.

Musically, Marley matured fast in this period, and he already had an incredible songbook, including classics like “Lively up Yourself”, “Trench Town Rock” and “Kaya”, which were to resurface in later years under Island Records, to which the band signed in 1972. Island relaunched the group in 1974 as Bob Marley and the Wailers (see box overleaf), with Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer leaving to pursue successful solo careers. Marley, meanwhile, went from strength to strength. Purists might argue that his new female backing singers, the I-Threes, were a poor substitute for the beautiful close harmonies of the original Wailers, and that the arrangements of his Island records conceded too much to the unsubtle demands of rock, but no one could deny the power of his lyrics, nor the magnetism of his performances.

No one could deny the phenomenon of his success, either, which placed reggae and Jamaica on the world map. Thanks to his powerful persona, and some shrewd marketing, Marley became a symbol of rebellion all over the world. This brought him enormous fame abroad – especially in Africa, where he had superstar status from Casablanca to Cape Town – and a very high profile at home. In such a politicised society as Jamaica, it also made him a target, and sure enough, he was nearly assassinated in the violent election year of 1976. Bravely, Marley decided to try to use his prominence to encourage peace on the island, bringing together the two party leaders at the famous One Love Concert in 1978.

Marley died of cancer in 1981. Peter Tosh was shot dead six years later in circumstances that have yet to be properly explained, after a turbulent career that had earned him many enemies, thanks to his uncompromising stances, particularly on the issue of ganja. Only the mystic man, Bunny Wailer, survives. He has been seen around more frequently lately, castigating young people for abandoning their roots and their principles, and receiving precious little respect for doing so.

After Marley, the other key singer in bringing the reggae sound to an international audience was Toots Hibbert, who joined Nathaniel Mathias and Henry Gordon to form Jamaica’s top vocal group of the 1960s, the Maytals, becoming the internationally known Toots & the Maytals in the next decade. Toots’ mother was a Revival Zion preacher, and he inherited from her his legendary impassioned groaning, which is clearly derived from Revival’s trumping tradition. Otis Redding and American soul also influenced Toot’s style. He missed the rock steady era while jailed for possession of herb (a stay immortalised in his classic “54-46 Was my Number”), but upon his release, the reunited trio blasted into reggae, with Leslie Kong-produced classics like “Pressure Drop”, “Bla Bla” and “Sweet & Dandy”.

DJs, Dub and Singers

By the close of 1973, Jamaican music’s two most radical and influential elements were established: the mixed-down dub form and DJ ‘toasting’ on record. Not surprisingly, both innovations grew out of the two institutions that have always been at the heart of reggae’s development: the recording studio and the dancehall. And one man played a central role in the origins of both: the popular sound system owner and master engineer, Osbourne Ruddock, aka King Tubby.

The jive talk of DJs had been adding to the excitement at dances from the late 1950s, when Coxsone had urged Count Machuki to shout his own catch phrases over discs (rather than simply introduce them). Tubby’s experiments in stripping vocal discs to their instrumental basics gave the man with the microphone the space to say a lot more than the occasional line or two.

Despite their following in the dancehalls, it was some time before the flamboyant characters at the mike made much of an impact in the studio. King Stitt – known as ‘the Ugly One’, because of a facial disfigurement – was the first DJ to consistently score on record, most notably with a series of early reggae hits for Clancy Eccles, such as “Fire Corner” and “Vigerton 2”. Yet these were still primarily instrumentals, featuring Eccles’ session band, the Dynamites, with occasional (but very effective) interjections from Stitt.

DJs only took centre stage when, significantly enough, the main man on Tubby’s Home Town Hi Fi began talking on record. Ewart Beckford, better known as U-Roy, made his first forays into the recording studio with interesting enough sides for Keith Hudson, Bunny Lee, Lee Perry and Lloyd ‘Matador’ Daley, but the hits only came when he tackled the (then) recent rock steady hits at Treasure Isle.

Rapidly following U-Roy’s phenomenal success – he held the top three places in the Jamaican charts for three months in 1970 – were a flood of records from other gifted DJs. His main rival was the equally distinctive Dennis Alcapone, though memorable discs were forthcoming from men like Big Joe, Charlie Ace, Winston Scotland, Lizzy, and Scotty, as well as DJs who were to become major names for the rest of the decade – I-Roy, Prince Jazzbo, Dr. Alimantado (under a variety of names) and Dillinger.

It was U-Roy’s style that continued to rule, however, at least until the rise to stardom of a dreadlocked DJ from the Lord Tippertone sound system. The man who called himself Big Youth employed a new chanting style and Rasta-inspired lyrics. And it was this approach that was to influence the next generation of DJs, including Trinity, Prince Far I, Clint Eastwood and Jah Lloyd. The dominance of Big Youth and his disciples was then to continue until the dawn of the ‘dancehall’ era at the close of the decade, when the likes of General Echo, Lone Ranger and Ranking Joe reinstated the U-Roy style.

Dub music also developed in its own right. Its spacey, trance-like nature attracts the mystic, and few were more mystical than Augustus Pablo, famous both for his production and his eerie melodica playing. His relationship with King Tubby (who mixed his early self-productions) was particularly fruitful. When Island UK released “King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown” – the version of a Jacob Miller vocal – it introduced many outside the reggae world to dub. The album of the same name became a milestone, and remains perhaps the greatest dub set ever released.

Also important in dub developments were Errol Thompson and Sylvan Morris, as well as Tubby’s apprentices, Scientist and King Jammy (later to be a major producer). Dub and DJ art added a further branch with the ‘dub poetry’ of Briton Linton Kwesi Johnson and Jamaicans Mutabaruka and Mikey Smith. Smith, a wonderful and radical artist, was another casualty of political violence, murdered by JLP gunmen in 1982.

In the mid-1970s, the music changed once more. At the forefront of this evolution was the Channel One studio, whose house band were the Revolutionaries, built around the powerhouse of drummer Sly Dunbar and bassist Robbie Shakespeare. Together, Sly and Robbie developed the rockers sound, initiated by Augustus Pablo, giving classic rock-steady rhythms a new, militant feel to great and popular effect. Their creative and innovative spirit is still very much alive, and they have been players and producers on many of the top reggae hits of the last thirty years.

The rockers sound gave a fresh lease of life to the vocal trio, an enduring feature of Jamaican music that had been a perfect vehicle in the rock-steady and early reggae periods. Groups such as the Mighty Diamonds, the Wailing Souls and the Gladiators scored a number of hits employing rockers rhythms – as did former rock-steady star and then member of Marley’s I-Threes, Marcia Griffiths. Chris Blackwell even sent the London-based (though Jamaican born) Ijahman Levi to Kingston to place his reflective songs over rhythms from the musicians associated with the rockers style – including both Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare.

The producer Joe Gibbs and his engineer Errol Thompson (the ‘Mighty Two’), produced their own, less subtle variation of the rockers sound, and were particularly successful with records from Joseph Hill’s Culture and the golden-voiced Dennis Brown, as well as the DJs Trinity, Prince Far I and one hit wonders, Althea & Donna.

Among the singers of this period, Burning Spear (Winston Rodney) stood head and dread above the competition. Originally from the Studio One stable, he achieved roots prominence in 1976 with two astonishing albums, Marcus Garvey and Man in the Hills. At a time when Bob Marley was gathering an international rock audience, Spear’s rootsier sound gained a massive following. His performances, too, were stunning, whirling away into trance-like heights. A staunch advocate of Rastafari, he is still particularly vocal about Marcus Garvey and the necessity of repatriation.

Equally committed to his own variation of Rastafarianism (which involves a central role for Jesus instead of Selassie) is Yabby You (Vivian Jackson). An impressive producer and vocalist, he took his name from the chorus of his initial Jamaican hit, the powerful “Conquering Lion”. No one was more ‘dread’ or patently sincere in his faith than Jackson, and both his and Spear’s work are required listening for anyone harbouring doubts about the positive influence of Rastafarianism on reggae of the 1970s. So too are the albums of the finest harmony group of the era, the Abbysinians. This trio of committed Rastafarians represented a different tradition from the Mighty Diamonds, who were direct descendants of the soul-influenced rock-steady harmonisers. The Abyssinians developed a far ‘dreader’, more African sounding style apposite for their messages of repatriation and faith in Jah.

Jamaica has maintained few self-contained bands, encompassing both musicians and singers, but after Island’s signing of the Wailers, a few such units emerged. One that Island signed up was Third World – a group made up of the sons of solidly middle-class Jamaicans, far removed from the backgrounds of most struggling performers at Channel One. Nevertheless, there was no disputing their musicianship, and they could be as roostsy as anyone when they chose to.

As the ‘roots’ era drew to its close, another group stepped forward to take centre stage. Black Uhuru had already been through a couple of different line-ups when they added an American woman, Puma Jones, who perfectly offset the masculine tones and image of the group’s founder Ducky Simpson and lead singer Michael Rose. Produced by Sly & Robbie, they were widely tipped for international stardom, and to a degree achieved this, without ever filling the position left vacant by Marley.

Dancehall and Slackness

Throughout the period of Jamaican music when roots and culture were dominant, the centre of action and innovation remained the dancehall. This was where the hottest tunes could be heard on ‘dubplates’ (acetates) prior to their official release, and where new DJs made a name for themselves. Competition among the sound-system operators ensured constant musical change.

In essence, all Jamaican popular music has been meant for play in the dancehall. But the use of the word ‘dancehall’ to describe a specific style came about in the late 1970s, associated at first with producer Henry ‘Junjo’ Lawes, who began his rise to the top by recording a brilliant teenage singer Barrington Levy, over raw rhythms from what was to be the dominant session band of the new era, the Roots Radics. Lawes (who was shot dead in London in 1999) was to go on to produce practically every major name of the early 1980s, including the man who combined the techniques of singer and DJ, Eek-A-Mouse, and the top chatters like the albino Yellowman (whose Jamaican popularity was on a par with Marley’s), Ranking Toyan and Josie Wales.

Lawes didn’t launch his own Volcano Hi Power sound system until 1983, but among the exciting sounds that had come to rock the dancehalls were Gemini Disco, Aces International, Metro Media, Killimanjaro, Virgo Hi Fi and Black Scorpio, alongside veterans like U-Roy’s Stur-Gav Hi Fi, Prince Jammy’s High Power and Ray Symbolic. Each had its own young DJs and singers, and exclusive dubplates. The former African Brother and Studio One singer, Lincoln ‘Sugar’ Minott was producing himself by this time, and the Youth Promotion sound he set up drew on the burgeoning youth talent of the Kingston ghettos to become another major player.

By 1980, more records by DJs than singers were being released in Jamaica. Led by the outrageous Yellowman and General Echo, many made their name on the ‘slackness’ (obscenity) of their lyrics – a far cry from the spirituality of Marley and Burning Spear. Dub-poet Linton Kwesi Johnson saw the change as “a reflection of the serious decline in the moral standards of Jamaica...and in itself a reflection of the decline in the economic welfare of Jamaicans, and the whole dog-eat-dog ethos of the prevailing ruling party.”

Certainly, the programme of IMF-sponsored monetarism espoused by the JLP (Jamaican Labour Party), which won the election in 1980, was much harsher than the non-aligned socialism of the previous incumbents, the PNP (People’s National Party), and recession hit Jamaica hard in the 1980s. But not everyone chatted slackness. Rasta DJs, like Charlie Chaplin, Josie Wales and the very influential Brigadier Jerry, were a prominent part of the scene, as was the locks-wearing crooner Cocoa Tea, whose voice was as sweet as his name. The most prolific Jamaican vocalist of the 1980s, Frankie Paul, observed things with just as sharp an eye as the DJs, and commented on love, culture and the dancehall itself, as did his main rivals in the dancehall, Johnny Osbourne, Half Pint, Barrington Levy and Little John.

The most original vocal stylist of the period, Ini Kamoze, bypassed the usual sound-system circuit, making a classic album with Sly & Robbie in 1984. However, it wasn’t until a decade later that he had a massive and much-deserved US pop hit with his reworking of the song “Hot Stepper”.

Ragga

Jamaican music is a faddish beast, and before long things changed again. As had happened so often before, the initial changes were technological. Digital technology meant you could make tunes with only a couple of musicians – usually a bass player and a drummer. New rhythm tracks then became much cheaper to build, and production costs were further reduced by the extension of an established trend – that of the version.

Versions are reworkings of an original tune, sometimes from a different producer and set of musicians, and at other times employing the same rhythm track as the original hit, but with new mixes and fresh DJs (or singers).

The first digital record was a King Jammy production, Wayne Smith’s “Under Me Sleng Teng”, produced in 1985. The rhythm – loosely based on Eddie Cochran’s “Something Else” – has been used endlessly since, and is as much a dancehall staple as the Studio One chestnuts. After this groundbreaking tune, Jammy’s sound was the dominant one of the 1980s, with DJs like Chaka Demus, Admiral Bailey and Lieutenant Stitchie – as well as the singers Pinchers, Nitty Gritty and King Kong – available and on call. Interestingly enough, the DJ who became ragga’s first international icon, Shabba Ranks, had his first Jamaican hits for Jammy’s incredibly successful label, but only fulfilled his true potential for other producers.

Many of the early digital tunes now sound very thin, but some producers used the new technology to make some very serious tunes indeed. Foremost among them was, of course, Prince/King Jammy, but there was also Augustus ‘Gussie’ Clarke, who set a new standard with his production of Gregory Isaacs’ “Rumours” in 1988. Equally crucial sounds came from Jammy’s former employer, King Tubby (who went from mixing other producers’ tracks to launching his own Firehouse and Waterhouse labels), Bobby Digital, Winston Riley, Hugh ‘Redman’ James, Mikey Bennett, Steelie & Cleevie (a bassist and drummer who also played on most of their rivals’ productions) and the Penthouse Studio maestro Donovan Germain. Their new music was generally up-tempo, with heavy, rumbling bass lines that were admirably catered for by the vast bass speakers sported by the modern sound system.

The digital DJ of the eighties was characteristically ragga – ragamuffin in style and attitude. Ragamuffin was to the digital age what rudeboy was to the late 1960s – the essence of a bad, street attitude whose proudest boast is that “we run tings, and tings nuh run we”. Hot lyrical themes were crack cocaine and guns, a reflection of the state of Kingston at the time. In contrast to the braggadocio of the rough and tough DJs were gentle love songs – often covers of US soul hits – from sweet-voiced singers like Thriller U, Wayne Wonder and Sanchez. These were firmly in the tradition of late 1960s rock steady, and form a side of the ragga revolution that’s generally been ignored by outside commentators.

Sex – one of the mainstays of ragga tunes – also received some radical treatment as women DJs like Lady Saw answered male slackness on its own raunchy terms. Another gifted woman at the mike, Lady G, concentrated mainly on cultural material, often from a refreshing woman’s perspective. It was a surprising shift considering how curtailed women’s roles had been in the Jamaican scene. There has only ever been one female producer, Sonia Pottinger, who had her heyday in the rock steady era, and female singers have either sung love songs – lovers’ rock, dominated by UK reggae singers – or, like Bob Marley’s I-Threes, sturdy Rasta lyrics.

These days, however, women assert themselves on the dancefloors. No dance is complete without a women’s posse dressed to kill (the current style is bare-as-you-dare plus platinum-blonde wig), winding and grinding with whoever dares take them on. There is even a dancehall queen, and numerous princesses who often have day jobs as models and who have become as much in demand as DJs themselves. Male fashion remains more cautious, but behaviour from both sexes on the dancefloor is ever more extrovert. People started out carrying lighters to the dance, flashing them for any particularly wicked selection. Now some use gas canisters, igniting the spray to produce six-foot jets of flame in time to the beat.

Reggae’s internationalism has resulted in huge global influence for Jamaican music. Versions, remixes and raps – staples of the modern music industry – all stem from Jamaica. American hip-hop and rap have had some reverse influence, too, showing up in tunes like the Sly and Robbie production “Murder She Wrote” deejayed/sung by Chaka Demus and Pliers. Artists such as these and Shaggy also experimented with R&B, scoring international hits with tunes like the former’s “She Don’t Let Nobody” (based on a Curtis Mayfield sample) and the latter’s “Oh Carolina”.

Return to Consciousness

By the 1990s a further shift had taken place in the dancehall, away from the slackness and guntalk that had made ragga notorious. During the last half of the previous decade, only Yami Bolo, Admiral Tibet and Junior Reid were regularly making records concerned with ‘truth and rights’, but this gradually changed. Two influential figures in this return to ‘conscious’ themes were a DJ and a singer from the Destiny Outernational sound system, Tony Rebel and Garnett Silk.

Chatting ‘cultural’ lyrics long before rasta values returned to fashion, Rebel also produced modern roots singers like Ras Shiloh, Uton Green and Everton Blender on his Flames label. His friend, the late Garnett Silk cut strong conscious tunes for leading Jamaican labels, and was signed to the US major Atlantic Records before his accidental death in a gas canister explosion in 1994. He left behind an inspiring body of work which can be heard most clearly in the styles of singers like Ras Shiloh and Peter Morgan of the vocal-harmony group Morgan Heritage.

The move away from lyrics glorifying gunplay received a further impetus after the violent death of the promising young DJ Pan Head in 1993. This inspired two incisive commentaries from fellow mikemen: Buju Banton’s “Murderer” and Beenie Man’s “No Mama No Cry”. Buju has continued in a largely conscious vein ever since, particularly impressing with his masterful Til Shiloh album. Two of the DJ stars who were most associated with slackness, Shabba Ranks and Capleton, turned in a similar direction. Indeed, the latter has even taken to wearing the turban of the strict Bobo dread culture of Prince Emanuel Edwards, while a new wave of similarly committed chanters have followed in their footsteps, including Anthony B and the very popular Sizzla.

Among the singers most successfully expressing the ‘new’ Rasta vision of the world have been Luciano, who has made two impressive albums for Island, Jah Mali, former London-resident Mikey General, Bushman and Everton Blender. Outstanding records from the rejuvenated Michael Rose (particularly with Sly & -Robbie) and Cocoa Tea have also contributed to the roots revival. The vocal harmony group also made a comeback with the Brooklyn, New York group Morgan Heritage – he five children of the singer Delroy Morgan – who first set foot in a Jamaican studio on a visit in 1995, and have recorded outstanding material ever since.

In terms of rhythm, there were two contrasting trends in the last half of the 1990s. Producer Dave Kelly’s “Pepper Seed” of 1995 initiated a fashion for minimal, incredibly infectious and strictly digital tracks, many of the strongest being built by a visitor from London, Paul ‘Jazwad’ Yebauh. Appearing on labels such as Mad House, Shocking Vibes, Xtra Large and 2 Bad, these are meant for maximum excitement in the dancehall, particularly when voiced by popular DJs like Bounty Killer, Merciless, Buccaneer, General Degree and Spragga Benz, or young pretenders Lexxus and the Ward 21 collective (who not only rap but build their own hardcore rhythms).

In contrast to the gruff, ‘badboy’ tones of many of the top men at the mike, there has also been the phenomenon of Red Rat and Goofy, both bringing a fresh adolescent sensibility to dancehall runnings. The new cultural performers sometimes voice the same hot dancehall rhythms, though more often favouring the alternate style on offer – fuller-sounding reworkings of vintage hits.

No DJ has enjoyed greater success over hardcore ragga rhythms during the last couple of years, however, than Moses Davis, aka Beenie Man (though arch rival Bounty Killer has run him a close second). Cutting his first record when only eight years old (‘Beenie’ means small), he has since developed into an artist of real stature, even entering the UK pop charts in 1998 with the catchy “Who Am I”.

The traditional love balladeer hasn’t been left out of the picture, either. Under the guidance of Donovan Germain, the soulful Beres Hammond – whose career dates back to the Zap Pow band of the 1970s – found favour with new audiences. Germain saw the potential of placing Beres’s warm, emotive tones over modern dancehall rhythms, and scored massively with the hit 45, “Tempted To Touch” in 1990. Hammond hasn’t looked back since, with a trailer-load of further hits.

The singing sensation of the last years of the Millennium, though, was Mr Vegas. This new boy on the block created the sort of pure dancehall excitement once associated with Barrington Levy and Little John. Whether he will develop into a lasting talent remains to be seen, but no one is hotter at present, which means he has the pick of every producer’s best rhythms. This alone will keep the momentum running, at least until the next hot new name appears.